When I was a teenager, I’d take the Q into the city for after school activities. Right before the train swept onto the Manhattan bridge, there’ll be an animation on my right side. Shapes! Colors!! Rocket ship!!! This led my way into the mayhem of Manhattan.

So, I decided to ask the artist, Bill Brand, how does it feel to hear that? His art, Masstransiscope, is a part of my childhood.

“It’s a part of your parent’s childhood too,” Bill told me with a laugh, “it’s nice.” He has a light hearted voice over the phone; the type of personality that makes you want to grab a beer and gab about his film preservation company, BB Optics. He wasn’t trying to make a big splash in this piece that took five years to make.

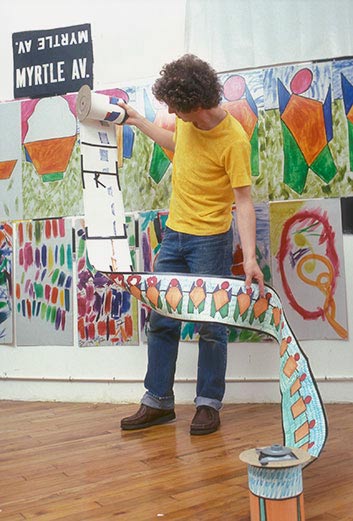

Bill Brand with a scroll of the animation.

Masstransiscope is a 300-foot painting with 228 slit. Each slit is about a half-inch wide and the painting is illuminated with fluorescent lights. This all started in the ’70s when downtown Manhattan was filled with abandoned buildings that artists would fill with art. Bill teamed up with Creative Time, an organization that supports public art, in order to make this happen. As an experimental artist, Bill had these questions of, “what is film? What is minimalism and conceptualism? I wanted to see how a piece would change for a large audience versus a small audience.” I made the assumption that he had a big source of inspiration but was pleasantly surprised when he paused for one beat, “well,” two beats, “I just wanted to see it.”

In 2008, Masstransiscope was restored.

Like anyone who makes art, he had challenges along the way. At first, he wanted to put up photographs and change them every week. “Each week would be a different shoot,” but as he rolled out tests, the medium and limits made the piece, “more abstract and flatter.” He noted where the train would slow down and where it would speed up. He created a zeotrope-esque machine that he used for a test and just recently took it out of storage. “It still works!” he said with infectious excitement. A zeotrope creates the illusion of animation in a circular motion. It’s a sphere with slits and drawings inside of it. The user looks through the slits and spins it to see the animation. The machine that Bill created, allows him to see how to create that illusion in a linear way — the way that the train passengers would see it. He tweaked Masstransiscope in order to make sure that no matter what, the illusion didn’t fall apart.

“When you’re an artist, you make work and you want it to have an impact. Not knowing what the impact will be,” Bill said when I asked him what it feels like to be a part of the New York landscape. “I like the fact that it’s in between being well known and being–” Bill stopped talking as he search for the right word.

“And being a secret?” I suggested.

“Yes!”

He’s right. It does. Masstransiscope comfortably hangs in that limbo. And, if you haven’t already, take the Manhattan-bound Q or B and join the rest of us on that secret.