Memories of a Master

by Richard Gorey and Mark Bailey

When a friend called to tell me that Ray Harryhausen had died, I was sitting at my drawing table on my light box, animating a Triceratops for a sequence of dinosaurs fighting I’m planning for my demo reel. To say Harryhausen’s work has influenced my life is an understatement. I literally would not have become an animator had it not been for his films– and I was pursuing that dream, and that craft, when I heard the news of his passing.

Then the emails and calls began: “If I had a nickel for every time you mentioned Harryhausen’s name,” and, “He was a huge part of our growing up, though we never knew him.” And on and on.

I never knew him either, sadly, though I met Harryhausen once when he visited ASIFA East, for his book tour. That night, I had the privilege of watching the famous skeleton swordfight from Jason and The Argonauts with the man who had created it. A nerd’s thrill, I admit, but I will never forget it, or forget the applause that exploded when the sequence ended. Harryhausen was older then, but still sharp; he spent the final years of his life basking in the adulation of millions of fans who swarmed to his personal appearances and book events and screenings of the films he made.

He has always been my personal and professional hero, but not merely because he crafted the illusions that haunted my childhood: empty-eyed Talos turning to stare at Hercules in Jason, the terrifying Cyclops from 7th Voyage of Sinbad, the Allosaurus dying in the burning cathedral from The Valley of Gwangi…and so many others.

I admired…no, I worshipped those moments, and those films, but I admired just as much Harryhausen as a professional and as a person. He was a class act who never had an unkind word for those he’d worked with. He was dedicated to his art and to the film industry, and he was willing to work, and work and work, to deliver the sequences he had designed on the drawing boards. Actor Gary Merrill, who appeared in Harryhausen’s Mysterious Island (1961) once visited the effects artist in his studio while Ray was animating the famous giant crab scene from that film. “God, the patience,” Merrill later said. “I asked him, ‘Ray, how do you stand it?’”

Many people can’t. Each year as a teacher of animation I see dozens of students discover that they can’t tolerate the tedium, the repetition, and the commitment that animation demands of those who practice it. Author Jeff Rovin described Harryhausen’s gifts in another way. He claimed that the creatures and monsters animated by Ray’s disciples “simply moved…Harryhausen’s lived.”

How very true. Harryhausen was a student of theater, of the Greek myths, and of acting. He took up sword fighting when he had to animate the climax of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, so he would be more able to imbue the dueling skeleton in that sequence with personality and athleticism.

He often worked with difficult people: directors who resented the influence Harryhausen had on the films they were called in to shape themselves…or so they believed, at first. Harryhausen was a true auteur, in that his films were products of his vision, design, and intention. Though from time to time directors like Nathan Juran or Gordon Hessler could enhance the performances of the live actors, or maintain a breathless pacing in the works, audiences went to see “a Harryhausen film,” and cared less for the writing and acting than they did for the illusions and wonders presented in those matinee favorites.

It’s a shame that the other aspects of Harryhausen’s films have been maligned. There were occasional flashes of brilliance in them, and some of the performances, by actors who possibly knew they would be upstaged by Ray’s monsters, are delightful. James Franciscus comes to mind, in Gwangi, as does Lionel Jeffries, in First Men in the Moon, and Nigel Green in Jason.

These days we hear a lot about the death of traditional animation methods. An ex-Disney animator is holding a mock funeral for hand-drawn work, and is, I am told, hiring professional mourners to throw themselves over a casket draped with peg bars and animation discs. So many young people coming into the field ask questions about whether or not they will be “allowed to practice” in an industry dominated by greed, corruption, and the wonders of 3-D CGI work that many viewers find cold and synthetic.

Harryhausen, after finishing his first feature, Mighty Joe Young, faced all the same issues. He was told by his hero and mentor, the great Willis O’Brien, that “these films are becoming too expensive,” and was informed that outside the major studio system, there wasn’t a place for the kind of meticulous, hand crafted work he had a great passion for.

And so he left the majors, doing independent work for years until he partnered with producer Charles Schneer. Though they are cherished as classics today, most of Harryhausen and Schneer’s films were produced on low budgets outside of the studio system, with lesser known actors and location work that was grueling and debilitating.

Along the way, Schneer and Harryhausen had to deal with gangsters, extortionists, dysentery, financial disaster, sewage in the water hurled onto the actors for Sinbad’s storm sequence, and reviews that called their work “movies made by morons, for idiots.”

But over four decades, Harryhausen persevered. He didn’t wait for someone to tell him he had the permission to follow his dream: he went after it, and he worked harder than most people ever will, to make that dream a reality.

But that ‘reality” was a subjective thing. Over time, as CGI films began to dominate the box office, Harryhausen often heard the criticism that his stop-motion creatures were becoming passé: that the films felt very “rotary dial” inn a culture that demanded “realism” in special effects. Harryhausen responded, “It was never my intention to make my creatures (and they were ‘creatures,’ not ‘monsters’) look real. Of course, I tried to make the illusion of life seem persuasive, so that people could suspend disbelief, and relate to the story. But my agenda as a filmmaker was to invest each shot with the most drama and interest I could manage, in order to best tell the story.”

He succeeded. The best of his films are among the great fantasy classics, and the lesser films are entertaining and fanciful, but they are all defined by the artist’s taste, style, and love of classical literature and drama. His creatures, when they died, always died with a bit of tragedy and pathos. His sequences have a warmth and feeling to them that is hard to define and impossible to replicate, even with the advances in technology that have transformed the industry.

With the closing of so many modern effects studios and the economy still recovering, many young animators are wary of the industry, and frightened that they will not find their place within it. Harryhausen MADE a place for himself, and he worked constantly and consistently to ensure that his work would remain his own. Ultimately, he didn’t wait for permission, or good luck, or the benevolent hand of an uncaring studio head. He discovered his dream very young, when he first saw Willis O’Brien’s King Kong, at thirteen.

I have found that many, many young animators are inspired at such an age– but that over time, that dream, or specifically, that drive diminishes. For me, the lessons of Harryhausen’s life and work is that dreams aren’t free: they cost something. Sometimes they cost you leisure time, a personal life, and mainstream acceptance. But they are worth the price. They are always worth the price. And when I found myself, at fifty, drawing for the thousandth time that Triceratops lunging at that T-rex, I was glad I had been introduced to Harryhausen’s work– and work ethic. We animators don’t have it easy…but we do have our inspirations, and when we see something we have created move, and live…well, there’s nothing…NOTHING in the world like that thrill. I thank Ray Harryhausen for making his dream come to life, so thousands of other dreams could as well.

From animator and designer Mark Bailey

“Hoping to live by the words of Ray Harryhausen…” has been the opening of my bio for years. It came from a wonderful documentary included on The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms DVD where longtime friends Ray Harryhausen and Ray Bradbury swore to grow old but never grow up. This is where I took inspiration for living a creative life and trying to never lose a childlike sense of wonder.

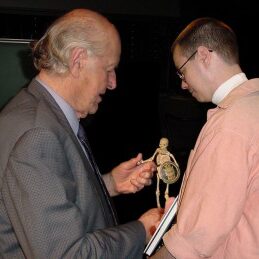

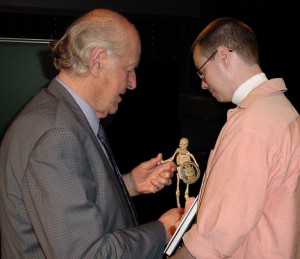

I was attending a Science Fiction convention on Long Island when I first met Ray Harryhausen. At one panel, he told us about the giant, cave-man menacing lizard that was filmed in One Million Years B.C.. In reality, the lizard kept falling asleep under the hot studio lamps, thus making the production even more challenging. During another panel, he discussed his body of work followed by a trailer reel of his films. Finally, he broke out a skeleton used for Jason and the Argonauts and the audience went nuts. Believing the day couldn’t be outdone, I walked around the convention grounds in a wonderful nerd fog until I bumped into him! Mr. Harryhausen and a handler were sitting alone in a vending area; he shared some of his M&M’s with me as I asked him a few questions about his work and for an autograph, pure heaven. I was already creeping towards my amateur film making endeavors, but a meeting with an unassuming and totally approachable Maestro helped push me to realize my own creativity.

A wonderfully moving and thought-provoking tribute from a true fan. So sorry the Master is gone, but what a life he lived and what an example he set!