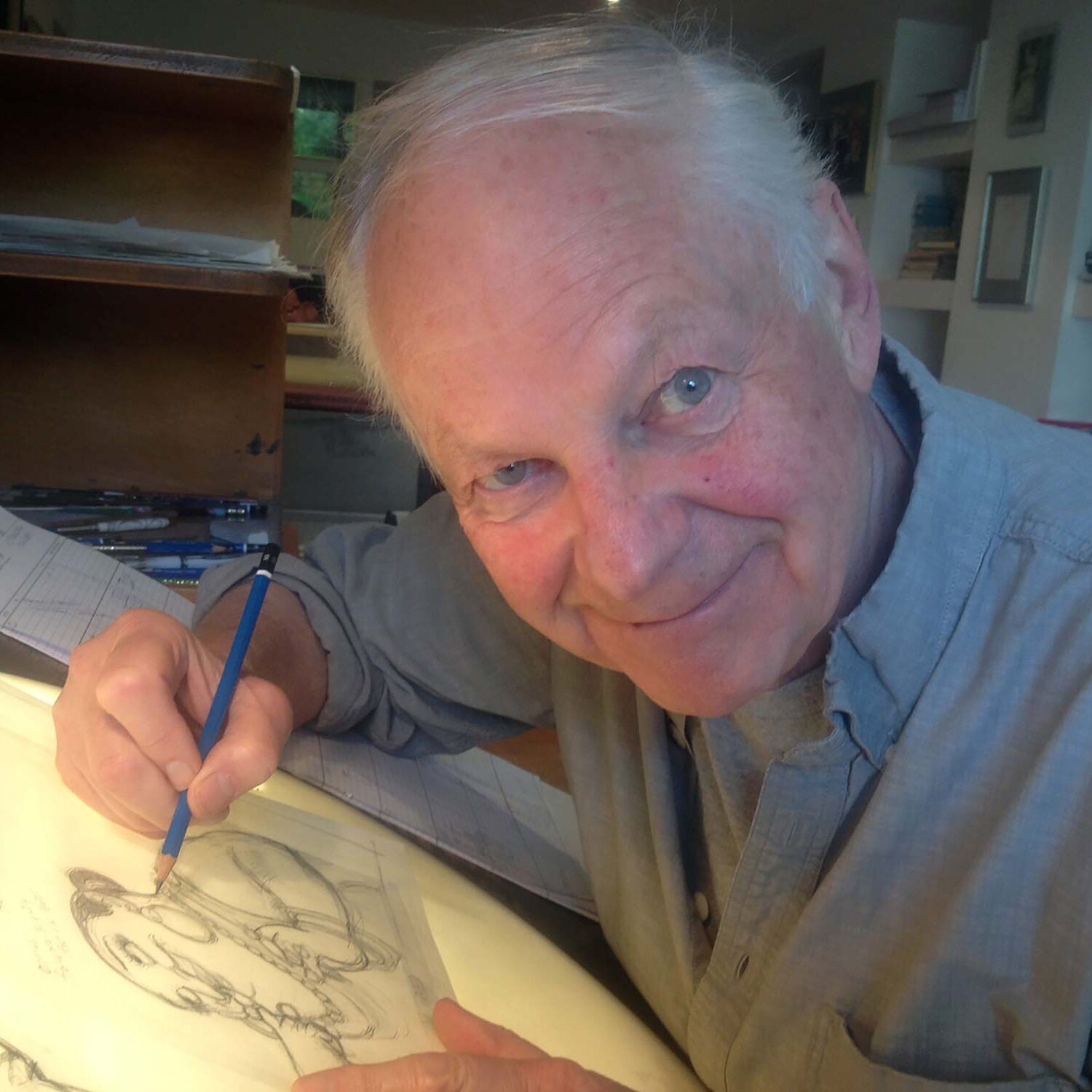

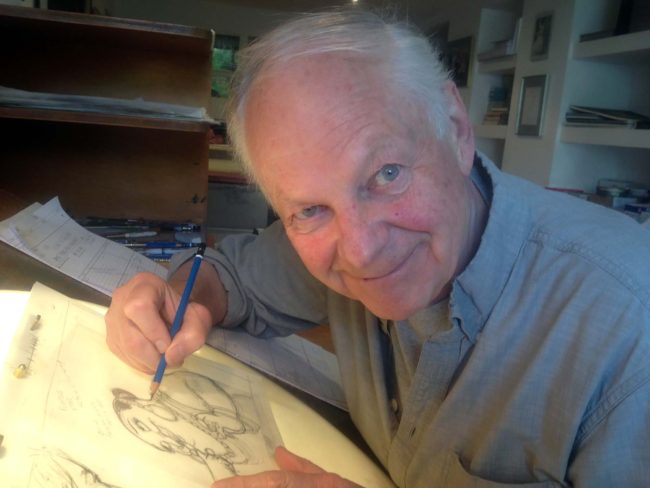

Richard Williams (photo from Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences: photographer unknown)

An animation legend left us today.

Richard Williams (1933-2019), at age 86, lived as long as many or most of us manage—but his surrendering this life hits unusually hard and unexpectedly, likely because surrender has never been Mr. Williams’s temperament, and because his outsized fervor and incandescent immersion in his art was larger than life. He was a brilliant artist, but his presence was mightier and more vast than that of any ordinary artist or, indeed, ordinary mortal. In whichever category we consider Mr. Williams—animator, director, studio owner, teacher—no words feel adequate to describe him, because these are all words for mortals. Richard Williams seemed other than mortal: not in the sense that he was incapable of death—which he managed early this morning—but in the sense that he spoke and lived as a man possessed of a greater force which worked through his hands and words. In that sense Dick Williams, while indeed an artist was, more fittingly, a prophet.

Mr. Williams so loved his craft, and served it with such profound devotion, that the genius of the ages spoke through him. Williams was himself, to be sure, endowed with genius: but the genius that spread in his wake was greater than his own. His lifelong, nagging thirst to improve his understanding of the craft led him to the masters of the generation before: animators like Art Babbitt, Ken Harris, Milt Kahl, who were indeed geniuses, but had not planned on being prophets. He sought them, during the last years of their careers and prime of his own (a prime that lasted decades), learned from them, and sometimes hired them: to animate, to teach. He absorbed and mastered their lessons thoroughly as the most devoted acolyte, and embodied them. Long after these men died, they lived—because their genius and their method were alive in Mr. Williams’s mind—if not blood.

Throughout his life he shared his knowledge and passion. The expression of this passion was not always appreciated by the money men (his exquisite, unfinished feature The Thief and the Cobbler was famously pulled from his hands, disfigured, and “released” with the same indifference with which a bank might repossess and sell off a car). But it was beloved by generations of artists. John Canemaker writes: “Dick was always open, candid, witty and unstinting in the information and entertainment that flowed from his vast life experiences.” Tom Sito writes: “We say in animation you have your biological fathers and your animation fathers. Dick was an animation father to me…. He made us who we are.”

Richard Williams: rest in peace.

—Ray Kosarin