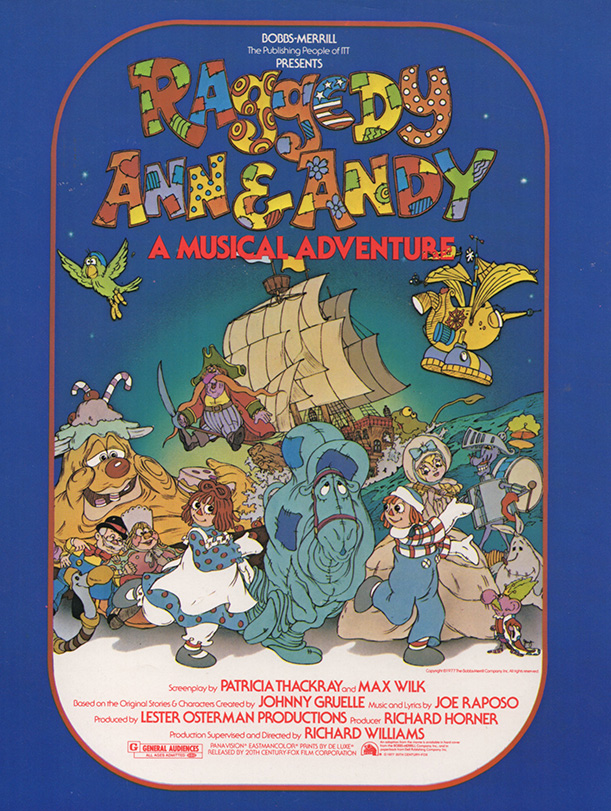

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the release of Richard Williams’s lavish—and in some ways landmark—feature-length animated confection Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977). The ambitious film, which initially received mixed reviews and tepid box office, has nonetheless been celebrated and regarded with affection by viewers who grew up with broadcasts on CBS and the Disney Channel and many within the animation industry. But its 40th anniversary could easily have gone unmarked. Not only did the film’s weak box office place it low in the esteem of current corporate owner Simon and Schuster; scandalously—according to animation historian and archivist Steve Stanchfield—at some point during the film’s 40-year course of corporate buyouts and attendant transfers of copyright ownership and physical assets, the film’s negative has gone missing. Happily, thanks to the efforts of this year’s “Animation Block Party” festival in residence at Brooklyn Academy of Music, the film was presented this weekend in a surviving 35mm Panavision print. Even better—in attendance for a Q & A following the film were animation historian and moderator Jerry Beck, Mr. Stanchfield, and two of the film’s artists: animator Doug Crane and assistant animator Dan Haskett, who shared personal recollections of working on the project.

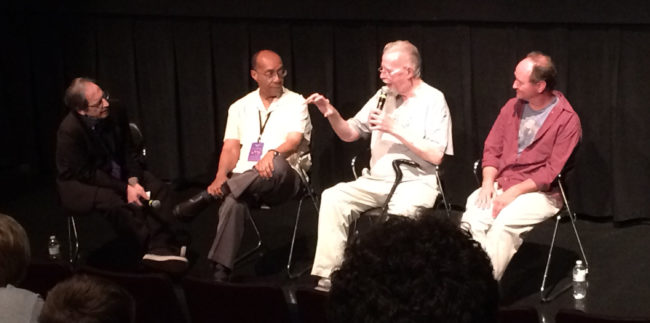

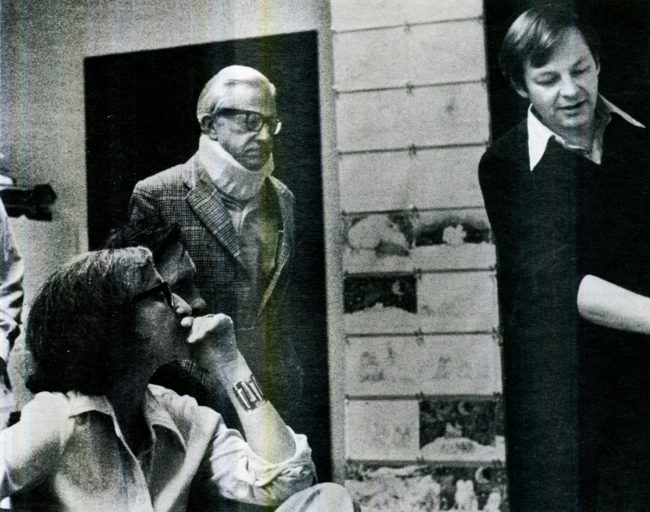

Moderator Jerry Beck, Dan Haskett, Doug Crane and Steve Stanchfield (photo by the author).

Raggedy Ann is both an important and interesting film, less because of its own sleepy, sugary story than the legends and lore attached to its making. It was an unlikely production at an unlikely time. First, there was the genesis of the project itself. Indeed, the chief motivation for the ITT-funded film, according to Stanchfield, was to burnish the company’s reputation (ITT had been battered from the unseemly timing of its contributions to the 1972 Republican National Convention while under Senate antitrust investigation, and its alleged financial ties to the 1973 Chilean military coup that installed Augusto Pinochet). Then, there was the eccentric production team in charge. Raggedy Ann’s producers, Broadway magnates Lester Osterman and Richard Horner, had never made an animated feature or indeed any feature film whatever. The composer of the film’s songs, rising star Joe Raposo, reportedly had an outsized influence on the overall production, which stirred rivalry and chaos. Not least, there was the unfavorable timing of attempting a non-Disney animated feature film at a moment, in the mid-1970s, when theatrical animation production had slowed to a trickle, non-Disney productions seldom made back their cost, and the talent pool of artists seasoned enough to manage theatrical-grade animation was dwindling, with scant new talent to replace them.

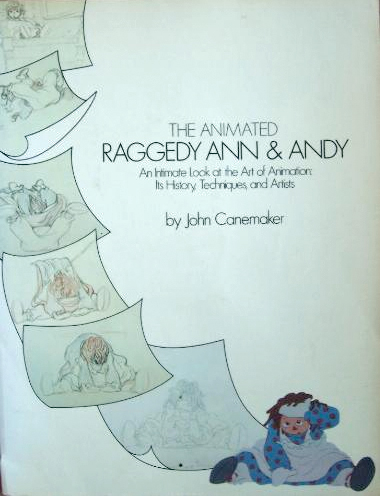

This last point, however, is precisely why this film holds special fascination for animators and historians. Here is a moment when accomplished young director Dick Williams, passionate enough to sign onto a massive project despite not yet knowing where he would muster talent to complete it; a handful of renowned master animators, most approaching, and some emerging from, retirement; and an eager army of aspiring young animation artists, with little professional experience and, till now, little opportunity to get it, all came together. The result, by all accounts of those who were there, was a special, once-in-a-lifetime animation boot camp. The ad-hoc Raggedy Ann production was not just a film—it was a hallowed passing of the torch from several of animation’s greatest living legends to a new generation. This story is largely known thanks to John Canemaker’s fascinating 1977 book The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy (apparently intended as a promotional book to accompany the film’s release, but which quickly settles into the real story—a rich account of the animation geniuses, their passions and quirks, and the secrets of their craft).

I feel personal connection to this film through my friendships with two of the film’s artists who have since left us—Tissa David, the brilliant principal animator of the Raggedy Ann character, and Michael Sporn, who supervised the film’s many assistant animators. A startling many of these apprentice artists went on to enjoy lasting success in the industry; several of them—including “Disney Renaissance” animators Eric Goldberg and Tom Sito— became legends themselves.

Tissa David, Art Babbitt and Richard Williams, during production of “Raggedy Ann” (1977, photo by John Canemaker, courtesy of Michael Sporn).

Animator Doug Crane (photo by John Canemaker, courtesy of Michael Sporn).

It is a rare treat to see this colorful, often-exquisite film, for generations seen only in non-HD broadcasts and noisy VHS tapes, in Panavision on the big screen. Watching the film is both a delight and at times, it probably ought be said, a chore. Mr. Beck, introducing the film, offered that the audience might best approach it as a “musical revue.” This is more charitable than belaboring the movie’s fundamentally weak story, but the underbaked plot and undermotivated characters give viewers of any age precious little to invest in: rag doll siblings Ann and Andy set off out their nursery window to rescue Babette, a stuck-up French doll they and we have only just met, from the amorous clutches of the rowdy toy pirate Captain Contagious, who has kidnapped her. The diversions that follow—which indisputably serve up vivid characters and sometimes brilliant set-pieces—offer little to no stake in the actual story and, moreover, in effect demote the central characters to little more than audience surrogates. Indeed the main story itself ultimately collapses: when at last Andy and Ann catch up with Babette, she has neither interest nor need to be rescued.

So while the best songs are pleasing, what is best to appreciate in this meandering film is the animation itself. The credits read like an A-list of talent from the “golden” age of animation at Disney, Metro and Warners, including Hal Ambro, Art Babbitt, Gerry Chiniquy, Emery Hawkins, Grim Natwick, Irv Spence and also Tissa David—herself an apprentice of Natwick, since graduated to master. The film’s pleasures are substantial and many. Corny Cole’s mischievous and meticulous production design grounds the outrageous people and places—and a watchful eye is rewarded with signature flourishes of the film’s animators.

Emery Hawkins’s “Taffy Pit” sequence (photo from Steve Stanchfield: “Emery Hawkins Greedy animation from ‘Raggedy Ann and Andy'” on Jerry Beck’s site Cartoon Research).

Probably the film’s most extravagantly animated sequence is the so called “Taffy Pit” sequence, deliriously animated (until time and money ran short) by Emery Hawkins. Imagine, if you can, an entire lake made up not of water but of swirling, sticky taffy—adrift in which are many, smaller candies and cakes. Next, imagine that this lake is, itself, a monstrous living creature—the “Greedy”. The forms of this creature emerge and vanish with the constant ebb and flow of the waves that ripple through it—his overbearing voice (by Joe Silver) resonates, but only intermittently do his eyes, mouth, or amorphous taffy appendages asynchronously emerge from the heaving mess, to feed into his insatiable mouth the swirling cakes, treats, and blobs of his own taffy self. The Greedy character, to be sure, is repulsive. But the endlessly evolving, virtuoso animation holds our eye captive. We delight in the miracle of the churning animation remaking itself, in meticulous rhythm with the character’s anguished voice, with the same fascination with which we marvel at the many players in a precision marching band weave in and out of unexpected, yet perfect, formation.

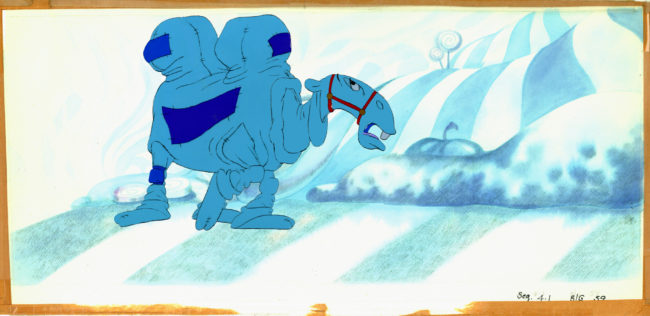

Cel setup of Art Babbitt’s Camel (photographer unknown: likely John Canemaker or Michael Sporn, courtesy of Michael Sporn).

The brilliant Art Babbitt—one of Disney’s most prized animators (until his conspicuous participation in the 1941 strike brought Mr. Disney’s contempt disproportionately on his own head)—beautifully animated the song “Blue,” featuring the “Camel with the Wrinkled Knees” (poignantly voiced by Fred Stuthman) lamenting his loneliness. Babbitt was valued throughout his career as an expert animator of dance (Tissa told me once, “you can learn to dance from his animation”); he brings to the camel both the technical precision to make this rag doll’s dance fully believable and the distinct, if quieted, comedy he brought to his animation of Goofy. Babbitt’s camel is sympathetic, funny, and splendidly drawn, his forms solid beneath his slumped wrinkles.

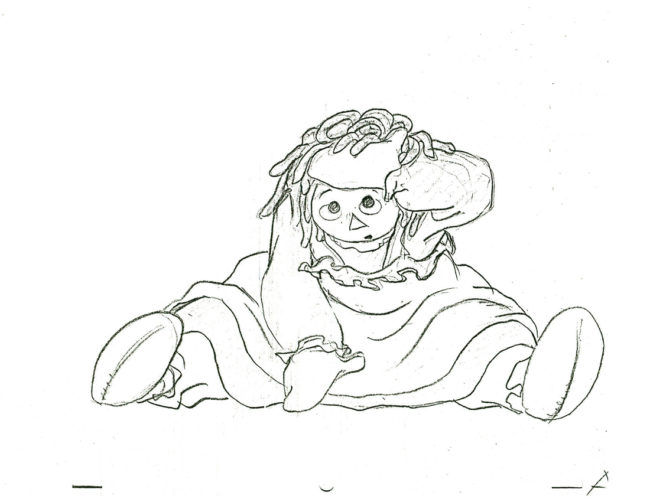

Raggedy Ann, drawn by Tissa David (scan courtesy of Michael Sporn).

But most magical for me—though I am of course biased—is Tissa David’s affecting animation of Raggedy Ann (voiced by Didi Conn). She animated Andy and Ann in their song “Candy Hearts and Paper Flowers”—but her other scenes in Tissa’s hand peppered through the feature sing with warmth. Always, no matter what she was animating, Tissa emphasized the importance of feeling a character’s weight in every action. In her handling of Andy or Ann, their weight translates, through the brisk sweep of her pencil, directly through the dominant forms of the character’s body and limbs, coming elegantly to rest in the wrinkles of their clothes. Where other animators opted for a more studied rendering of the dolls (including Williams himself, in Andy’s athletic and immaculately drawn “No Girl’s Toy” number) Tissa’s scenes overflow with bold intuition. Tissa’s Ann shares a special intimacy with the viewer, her eyes flirting, several drawings at a time, through the “fourth wall” of the screen—an indulgence that would certainly not be right for every character or film, but plays beautifully for her. It feels almost as if Ann is our doll—and whatever she may think, say or do she shares conspiratorially with us—the child whose imagination brings her to a life we share with her.

Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure is emphatically worth seeing and preserving. Its historical importance is clear: Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) and arguably the entire Disney Renaissance may not have come to pass without it. But it is also a treasure trove of masterful animated performances. Seeing this work brings much the same pleasure as hearing a favorite musician’s unreleased recording sessions. While we continue to appreciate better-known productions (with stronger stories), this 1977 time capsule of these formidable talents, most at the top of their game, is like a reunion with beloved old friends.

—Ray Kosarin