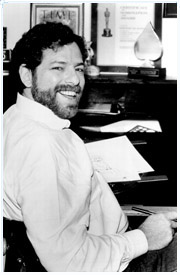

ASIFA and the New York animation community mourn the passing of a most extraordinary artist and friend—renowned animation producer and director Michael Sporn, who died January 19, at age 67, from pancreatic cancer.

Michael Sporn’s professional accomplishments are important and many. During over thirty years running his New York studio, Michael Sporn Animation Inc., he produced and directed circa thirty half-hour television specials for HBO, PBS, ShowTime and CBS, and many shorts, including many short film adaptations of classic childrens’ books for Weston Woods/Scholastic and scores of long-running Sesame Street segments. His films have won critical acclaim and countless awards, including five Emmys for his HBO films and an Oscar nomination for his celebrated short Doctor de Soto (1984). In 2007, Museum of Modern Art devoted a film retrospective and exhibition to Sporn’s life’s work.

Sporn’s career began in the early 1970s at a most inauspicious time for animation: theatrical shorts had effectively ceased the decade before; almost the only feature films in production were the few and flagging efforts from a dwindling Disney studio; and limited Saturday-morning television production, already migrating overseas, ground away at the remaining energy of industry veterans reaching the ends of their careers. Opportunities for unseasoned artists were scarce, the Union spurned new talent, and animation schools and training programs were few and far between. In 1972, after studies at New York Institute of Technology and a US Navy stint in Alaska, Sporn broke into the industry when John and Faith Hubley hired him for a three-day job as an assistant animator on a television spot. That three-day job, as Sporn liked to say years later, lasted for five years.

At the Hubleys’, Sporn honed his animation skills on commercials, industrials, television films and independent shorts including Cockaboody (1973) and Everybody Rides the Carousel (1975). There he also forged a close, career-long working relationship with master animator Tissa David (1921-2012), first a mentor and, years later, a key collaborator on his own films. He followed Tissa David to the Richard Williams-directed feature Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977) where he supervised the film’s assistant animators and inbetweeners. A return to the Hubleys’, followed by a stint at RO Blechman’s studio supervising commercials and the PBS special Simple Gifts (1977), led to a defining moment of Sporn’s career: his decision, in 1980, to open his own shop.

Sporn chose projects he felt worth doing. Short films led to longer ones; educational films and Sesame Street spots led to Sporn’s first children’s book film adaptations for Weston Woods and another milestone: an Academy Award nomination for his 1984 William Steig adaptation Doctor de Soto. Soon after, HBO entrusted Sporn’s lean studio with its first half-hour TV special: a musical adaptation of a children’s book by Bernard Waber (and the film on which I was first privileged to join his studio), Lyle, Lyle Crocodile (1987). This project also unexpectedly and forever changed Sporn’s life: if brought him together with his partner, Broadway singer and actress Heidi Stallings (Evita, Zorba, Cats). The couple, who married in 2010, collaborated on close to every other film from that day forward.

And there were many. And they were good.

Sporn threw himself into his work with rare integrity and passion.

His swashbuckling determination to make the films he wanted—even when this meant schedules and budgets that would frighten other producers away—meant the films got made. His most powerful films—films like The Marzipan Pig (1990), The Man Who Walked Between the Towers (2005) and perhaps his signature work, The Hunting of the Snark (1989)—likewise seized life and painted it with similar urgency. Few filmmakers, and precious few for kids, ventured where Sporn ventured. He tackled stories about hard and important subjects: social injustice, racism, economic inequality, drug addiction, terminal illness, the mystery and fragility of existence.

His insistence on portraying life’s tragedies and terrors hand-in-hand with its triumphs is a central reason his films speak so poignantly to viewers of any age. In an era in which kids’ entertainment has pandered ever more desperately to its viewers with syrupy half-truths, Sporn insisted on offering them something greater. He understood that, when he won his audience with the reassurance he was telling them the truth, he could take them anywhere.

The same frankness Sporn brought to his films he brought to most everything else. He eschewed pretension: he read critically and voraciously yet refused to call himself an intellectual; dressed simply, even when pitching a client or being fêted; never bullied the visitor to his studio with designer furniture or racks of his Emmy awards. Those lucky to know him—through ASIFA (he served on our ASIFA-East Executive Board for three decades), from festivals, or through working with him—knew only the real Michael: I’m pretty sure there was no other. His unflagging candor and conversational intimacy charged him with an ineffable charisma, and an evening with Michael talking about art or life felt a precious gift. He inspired a fierce loyalty in, it seems, nearly everyone who got to know him.

Working with Michael was exhilarating. His love of the films made you love them too. His studio atmosphere was perfectionism checked by humility: your work had better be good, but not conspicuous about it. Michael’s direction was firm but also intuitive and, wonderfully, open-minded. He’d hand out full sequences, casting animators according to their sensibility, and if you wanted to do a particular sequence, he almost always made sure you got it, apparently trusting there was probably a good reason it spoke to you. He made clear what he felt most at stake in the story but seldom gave too-specific directions, preferring to watch where your instincts carried the scene. When busy on a production, Michael moved swiftly and spoke little, which sharpened you to the small but critical signals whether you were giving him what he wanted. When OK’ing a line test of a scene you’d just animated, he might offer half a grin and say, “It moves,” then get on with something else. (It was some small comfort that that’s also what he usually said when reviewing a scene he’d just animated.) But when you gave him something he really liked, he’d often just say, “Great.” At least you were pretty sure that’s what he said. But he said it quickly, while already striding away toward his desk: no time for an end-zone dance. When the studio was humming, it felt like a large family, all cooking dinner.

The same sense of loyalty Michael inspired in person he inspired the world over through his remarkable blog (or “Splog”—as he named it). Following its 2005 launch, nearly every day for the next eight years, he wrote compellingly, passionately, often pointedly, about animation history and art and quickly won over a vast, new, international readership of animation’s top artists and scholars. Hordes of admirers who had never met him nonetheless enjoyed something of what it was like to hear him speak from the heart about his favorite subject. His thousands of posts remain a vast treasure trove of information and insight and testament to Michael Sporn’s robust knowledge and vigor.

The failure, then, of that same vigor in the final weeks of his life feels especially pointed. Even as we celebrate Michael Sporn’s work, we ache with the realization that we will not get to see his next films: those already in his head, like the feature film adaptations of the novels of John Gardiner and Elizabeth Taylor and the graphic novels of his friend Tom Hachtman, and his first feature film already in production, about the life and work of Edgar Allen Poe.

Michael Sporn is survived by his wife Heidi Stallings, sisters Patricia Sherf and Christine O’Neill, and brothers Jerry and John Rosco.

—Ray Kosarin

What a wonderful tribute. Michael was the best kind of man – brilliant, kind, generous, low-key, hilarious and so, so smart. An artist in every sense. Thank you for writing such an insightful piece about him. I really enjoyed it.

A beautifully written piece Ray.

Ray, This is wonderful passionate , tribute to Michael, and it was my pleasure to read it an learn about his many accomplishments and remember what an unassuming yet brilliant person he was. When I got my first Sesame St spots Micahel showed me how to handle the work, recommending people to help and animate along with me ( I animated some of the spots) and what to charge and everything else I needed to know and completely encouraged me. I was sorry I didn’t keep in touch more over the years…and one excuse is I live in California ( but not a good reason) , but we did keep in touch a little through Facebook. He will be missed by many I am sure.

Ray this is astonishing. Brilliantly written and constructed. It is a complete portarait of the artist as a man of dignity, warmth, humor and swashbuckling energy.

Michael was all of those things, Heidi. I much hoped for us to do Michael justice — and am deeply moved if you feel we have.

Ray, your tribute to Michael, so heart rendering & beautiful. I met Michael, for the first time, just this November. He was

interested in my animated musical short. I showed him my storyboards and sang my score. He wanted to Direct. I was in

Heaven. I loved his work.

We had some great talks on the phone about how to proceed on the film. I knew him for such…a brief time. But, I was

really touched by him. Not just by his artistic genius, but by his kindness. A sensitive, unpretentious man. A true Visionary.

The Bravest Swashbuckler, to the end.

Dear Heidi,

We received the sad news of Michael’s passing from a mutual friend now in Taiwan. I first met Michael when we worked together on “Raggedy Ann”. Michael was a big help and a loyal friend. Later he brought me in as an animator at the Blechman Studio. I always admired Michael’s drawing ability and he regaled us with signed copies of his illustrated books. Our last meeting with Michael, before our move to California was when we said “goodbye” at the Russian Tea Room. It was a memorable dinner and I will always cherish his friendship.

The tribute to Michael written by Ray Kosarin was very fitting and well deserved.

Our deepest sympathy and sincere best wishes to you, Heidi, and to Michael’s family. Millie and Cos Anzilotti