“I hate myself.” ~ Anna Sasaki

On Friday, Feb. 27th, the Director’s Guild of America New York Theatre threw open its doors and welcomed the start of the New York International Children’s film festival. Opening night included the east coast premiere of Shaun the Sheep The Movie and the North American premiere of When Marnie Was There.

When Marnie Was There is the latest animated feature film from Studio Ghibli, directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi (The Secret World of Arriety) and based on the novel by Joan G. Robinson. Robinson is a children’s book author and illustrator in the United Kingdom, and wrote young adult novels as well. The novel was first published in 1967.

From the NYICFF’s website:

- “When shy, artistic Anna moves to the seaside to live with her aunt and uncle, she stumbles upon an old mansion surrounded by marshes, and the mysterious young girl, Marnie, who lives there. The two girls instantly form a unique connection and friendship that blurs the lines between fantasy and reality. As the days go by, a nearly magnetic pull draws Anna back to the Marsh House again and again, and she begins to piece together the truth surrounding her strange new friend. … , When Marnie Was There has been described as “Ghibli Gothic,” with its moonlit seascapes, glowing orchestral score, and powerful dramatic portrayals that build to a stormy climax. In Japanese with English subtitles.”

I really like “Ghibli Gothic.” I think we can do an Elegant Gothic Ghib-lita costume for Halloween this year.

This is the first year I’ve attended opening night as a special guest to the reception and not as a volunteer. It was quite fun and interesting and gave me a chance to catch up with some NYU friends, as well as meet new people. And unusually I took notes during, not after the movie. Maybe not the most polite thing to do, nor the easiest in the dark, but we all have to try new things. While preparing for this article, I’ve decided it’s important not to spoil the plot, so I will avoid any and all dramatic revelations.

The movie kicked off with a full start. A crowd of children swarm over playground equipment, jumping, running, laughing pushing poking and who knows what else in a cloud of activity that only later reveals itself to be an animated achievement of excellence. We are introduced to Anna, one of the children from the older classes who have been assigned to sketch what they see. While other girls sit together and talk more than they draw, Anna sits alone and renders out a detailed sketch of the background, with only a couple kids in it (probably worthy of Parsons.) “I hate myself,” says Anna. I hate myself! Not five minutes in to this Anna has blocked out the joy of life around her and submerged herself into angsty teen despair. And as if this Japanese emo moan wasn’t enough, she keels over in an asthmatic attack.

The end.

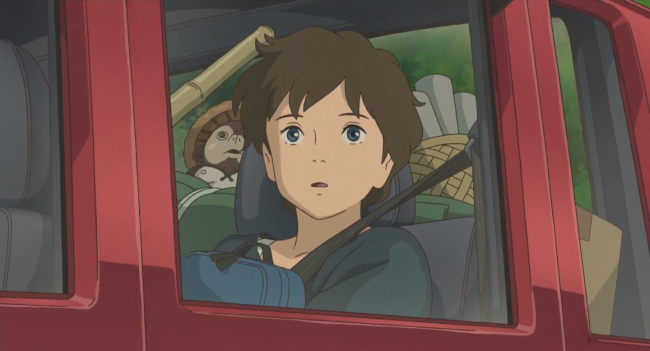

Ha ha, no. Anna lives in Sapporo, Japan (the northernmost island) and it is decided that she should be sent to the Hokkaido (“Northern Sea Circuit”) Prefecture to breathe fresh air and recover her strength for the next school year. [I find it interesting that this is the 2nd film that Yonebayashi has directed in which a child is sent on vacation to recover from illness and winds up on an adventure.] As Anna is picked up by strange new relatives from the train station, we learn more about her depression. I would like to know how it is in Japanese, but the current English subtitles describe her anguish over her “ordinary face.” Perhaps this will be easily translated in the inevitable English dub, in the style of The Incredibles or Coraline, but coming from a story written by a Buckinghamshire English author and adapted into Japanese anime, I feel like there is a different more subtle meaning. Inside the tiny car, Anna is packed in along with many groceries and supplies. When the car hits a pot hole, it seems like Studio Ghibli delights in filling the mis-en-scene with as much as possible. A strange racoon-bear statue in a rice hat delightfully bounces in the air with a glazed grin.

In response to suddenly being transposed to the Berkshires of Japan, Anna turns to sketching as a coping mechanism. She finds a derelict home, the Marsh House, that captures her eye. Anna is prone to falling asleep in the middle of her adventures, and after the first occurrence she discovers she’s trapped at the house by the rising tide. (Anna also trips a lot, like 5 times dramatically, which is probably an anime tactic). She is rescued by Toichi, a hermit in a rowboat. “He’s a bear, or maybe a sea lion.”

After a while Anna is encouraged to interact more with the local girls her own age. She is invited to a festival where kids carry paper lanterns and receive candy door to door. Anna’s aunt gives her a traditional yukata (dress robe) to wear (a hand me down from the aunt’s own daughter, now some hipster yoga teacher in the city). Anna’s reluctance to wear the yukata is the first sign of a troubling global-earth dynamic in this Japanese story.

During the festival, one spunky girl tries to connect with Anna, but the girl makes the wrong comment, singling out a certain otherness in Anna. Anna lashes out, because she is self-absorbed, and this leads to the most interesting statement of the movie: “You look like just what you are.” A sentence that neither condemns nor praises. And an idea that must be preserved from Americanization. I believe it means that Anna thinks her appearance defines her self. She clearly hates herself, for mysterious reasons involving her mother, and the multicultural community.

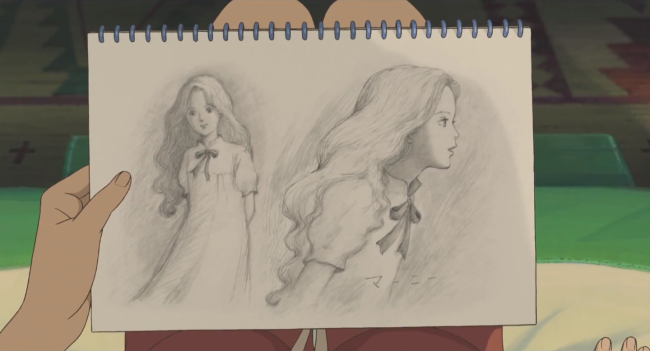

Anna flees the festival, and returns to the Marsh House, where she meets the mysterious Marnie. While Anna is a mousy flat chested girl with a ‘normal face,’ the short brown hair of a tom boy, and dresses in shorts and t-shirts, Marnie is a glowing vision with billowing blonde hair and the ability to fill white nightgowns with grace and volume. It is here that Anna’s world begins to break down. She is entranced by her new secret friend, and deliberately ignores the conflicting realities of the Marsh House’s derelict and occupied states. She trades in her own security and well being for the magnetic draw of Marnie, not caring what happens to her body at the end of every play date.

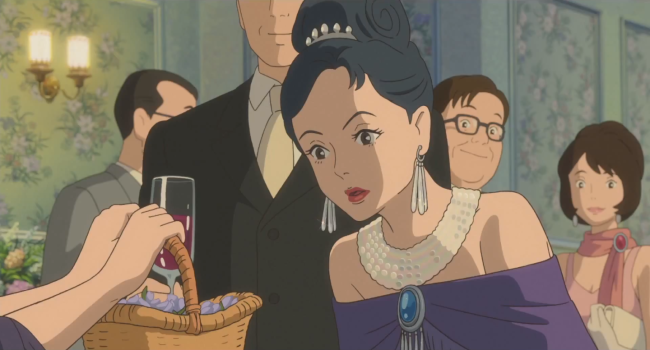

On one great occasion, Marnie invites Anna inside to one of her parent’s fabulous parties. Now, neither of Marnie’s parents are blonde. And her mother isn’t exactly a flapper. I was wondering what the background of Marnie was supposed to be. The parents leave her in the vacation house for months at a time, taken care of by a grandmother/nanny and two maids. In the late 1800s, northern Japan was trying to modernize itself after its great opening to the West, but also prevent incursions of Russian power from Vladivostok. But if this is a British book from the 1960s, it seems unlikely that Americans would live there so shortly after WWII. The name “Marnie” is Scottish (and/or British and Jewish) and means “of the sea.” And the guests at the party flash cash from all over the world. It is possible the answer lies in the original text, but it is likely that Marnie represents all of white society, a permanent outside of Japanese culture.

The rest of the film deeply intensifies the relationship between super-femme Marnie and tomboy Anna. Anna is disguised as a flower girl at the party, and has her first sip of wine. The party is a glamorous affair, reminiscent of galas in ballets or operas, and filled with lights touches such as a stocky mischievous woman giving a musician a drag of her cigarette while he plays the accordion. After seeing Marnie dance with the handsome Kazuhiko (Karamazov perhaps?) Anna finds herself learning to waltz with Marnie in the moonlight (Anna takes the gentleman’s stance but it is Marnie who truly leads). As the days pass, Anna discovers that the Marsh House has been sold and is being renovated for new owners, which leads to a disappearance of Marnie. When they finally reconnect in the dreaming world, Anna says, where were you, “I kept calling you in my heart.”

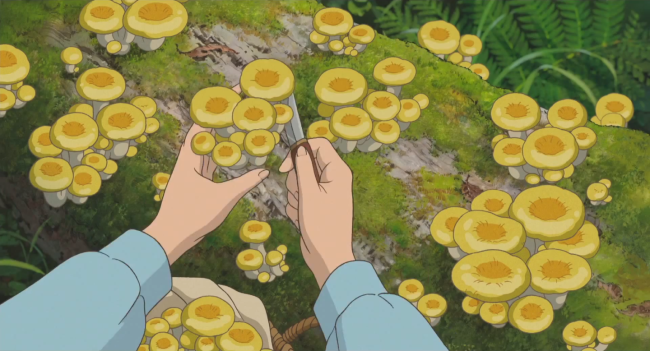

Illustrating the relationships and characters of the movie are Studio Ghibli’s standard art of nature. Scenes range from close ups of beach wildlife, clovers and sand-pipers, walks through the forest cutting mushrooms and talks in the kitchen cutting tomatoes (the likes of which you have never seen in an animated film). The environment is painted so thoroughly that it grounds the history of the Marsh house in a very real way. And makes it all the more crushingly real once everyone’s secrets fall into place.

Anna emerges victorious. She loves herself. When Marnie was There is a film all about love, and the beauty of the story is that it provides a love story for everyone’s circumstance: the love between teenagers, the love of a mother and daughter, the love of your own self, and the love of art. Just in case you wanted to know, Anna uses Kuenstler drawing pencils.

When Marnie was There has an encore this Saturday at the SVA theatre 2pm. It’s sold out, but I know the kids festival does use waiting lists if you want to try to squeeze in. Otherwise we can wait till an inevitable release in the future. Don’t forget to use your special ASIFA discount code to check out the festival’s other shows.

UPDATE 5/13 Tickets on sale NOW. Opens Friday May 22nd (my birthday!) at IFC in New York City http://bit.ly/1icBqI6 for one week only!