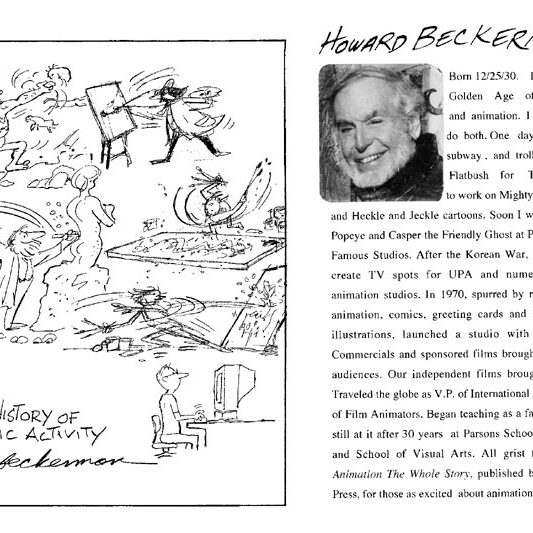

Introducing a new continuing monthly feature of ASIFA-East’s online Exposure Sheet, The ASIFA-East Interview. It’s no secret that the New York area contains some of the richest talent working in animation today. In an effort to better record our ongoing history we are proud to present this first installment, an interview with animation legend, and longtime ASIFA-East executive board member, Howard Beckerman.

1-Who were your animation mentors, where did you meet them, and what did they teach you?

Irving Spector at Famous Studios, was my mentor. I learned from many others, but it was Irv who pointed the way. He gave me a base. He was a good animator, a very good writer and well read. I had always wished to be an animator and to also write cartoon stories. He did all of that and I guess he understood that about my goals. He filled me in on how to approach animation timing, design and story. I was an in-betweener and when he took breaks from his own tasks he would stop by my desk. I would show him character drawings I had done on my own. He would cover my drawing with a blank sheet of paper, on the light board, and sketch over it describing a surer line and sturdier forms. I also recall Al Eugster, at the same studio, putting down his pencil and patiently explaining the making of field guides and exposure sheets. There were many animators who would rarely show you anything, so these moments were golden. Today I teach all aspects of animation to young people, partly because I enjoy it, but also to carry on the tradition of guidance extended to me by those experienced, good natured and self-assured guys.

2-Animation history tends to gravitate towards honoring the same set of names again and again. Who are the unsung animators you encountered over the course of your career and how should they best be remembered?

I worked with wonderful animators from all over, but my experience in New York leads me to mention a few that are not normally noted. I was always impressed with the personal approaches to the medium by Jack Schnerk, Ed Smith, and Paul Fierlinger and the skills, and calm, assurance of Nick Tafuri, Al Eugster, and Orestes Calpini.

3-How did you end up in animation? Was this something you wanted to do as far back as when you attended the High School of Industrial Art?

It was what I most wanted to do since I was nine years old. I had wanted to do comic strips, but when I saw Disney’s Pinocchio, I set my goals to get into animation. Out of school I was lucky to land a job with Terrytoons. Eventually I did do some comic strips and other non-animation work.

4-You left animation a few times in your career, most notably doing Illustrations and gags for greeting cards. What kept bringing you back to animation?

This question might also be, “Why did I leave?” During the years of active cartoon TV commercial production, there were 30 or 40 animation studios in Manhattan. Layoffs were always a possibility and then I had to find other things to do. Also, I would get impatient with what we were doing. From time to time I would yearn to do other things, to be more involved creatively and not be limited to the whims of advertising agencies. As a result, I did comic strips, freelance illustration, writing and some comic book pages. I worked on funny greeting cards at Norcross for a few years and that came about as a result of a recession in the animation field. I went back to animation every time because I love it, but also because I got calls from studios. I feel that my most satisfying animation experiences were at the UPA New York studio and at my own studio because in both places I was I could be totally involved creatively in aspects of animation production. People outside the field are usually impressed if you’ve worked on some glamour job, say that you animated a broom in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. What they don’t realize is that creativity extends to even the most mundane jobs, and that fulfilling these assignments can be creatively engaging, satisfying and rewarding. It’s about problem solving.

5-As a long time teacher of animation students at schools such as Parsons and SVA, what would you say animation education is getting right and what does it get wrong? And, how would you describe your approach to teaching animation?

Since each instructor or school has an individual approach, I can only talk about my personal slant on teaching the subject. I learned to animate by working many years in the shops. It was a one-to-one experience, working with specific animators, as well as a by-the-seat-of-my-pants thing tackling problems day-to-day and practicing at home. My intention in teaching is to give students the knowledge and experience of traditional techniques. Those skills are important and they give the student something to bring to the computer. The other thing I try is to encourage students to be versatile, the way I had to be in my career, and which is even more important today. They have to be ready to do everything. Most important is what they will learn on their own by just being observant of society and the world around them.

6-How did you develop your talent and affinity with writing that you used to write shorts while at Famous Studios (The Trip) and on your own award winning shorts (Boop-Beep)?

For me it was a long process. When I was a teenager and already interested in animation, I wished to do my own films. I created stories, scenes actually, but not yet full stories. It was frustrating. Although I had been an active reader and a moviegoer since I was 6 or 7, I didn’t yet understand how stories were constructed. When I began working in the field I saw how things were done and one day a complete narrative sprung into my head. I wrote it down and reworked it a little and, well, there it was~a humorous story. Actually, it was a monologue with a plot. I was going to art school after work and one night they had a talent program in the auditorium. It gave me an opportunity to deliver the monologue to an audience. It went well and it was my entry into realizing a basic thing about stories, which is that you start with a premise and then hang gags or incidents on to it. A premise begins often as “What if such and such happened?” or “How come things are like that?” Most of my other stories came about the same way. I sold my first story to UPA for their Boing-Boing family television show. This story also started with a premise and was made into a cartoon short. But I learned more about story from scripts that I was handed to develop as storyboards. Usually there were things lacking in the structure and while searching for a solution I discovered what the script failed to clarify. One example was a script that, strange as it may seem, neglected to include a locale for the story. Once I found a proper setting for the action everything else fell into place giving the story a stronger logic and visuals that were more connected and engaging. The Trip and Boop-Beep both began as premises. The first was suggested by a guy attempting to escape a repetitive job in conformist, modern society. Boop-Beep related to my desire to incorporate the theatrical stage routine of “blackouts” into an animated story.