Animation Goggles

Just over ten years ago I sat on my first animation festival jury outside of ASIFA-East’s annual jury screenings. It was The New York Expo, a now-defunct film festival that had been around for decades. I’ve since sat on a few other juries, most notably for the PISAF festival in South Korea. While on a festival jury you watch a lot films, take notes in the dark (so you can remember what you saw), and then gather as a group to discuss the films and choose the winners.

Just over ten years ago I sat on my first animation festival jury outside of ASIFA-East’s annual jury screenings. It was The New York Expo, a now-defunct film festival that had been around for decades. I’ve since sat on a few other juries, most notably for the PISAF festival in South Korea. While on a festival jury you watch a lot films, take notes in the dark (so you can remember what you saw), and then gather as a group to discuss the films and choose the winners.

One of my co-jurists on The New York Expo was a very sweet older woman who had worked as a background artist, and I recall she would only evaluate films based on their design merit. It was as if she saw no other aspects of a film. She never said anything about a film’s writing, animation, pacing, humor, storytelling, directing, or soundtrack. Her “animation goggles” saw only production design. I can’t say this made her the ideal jurist, but she certainly had a clear point of view that she processed all animation through.

As the years rolled on, I have to come to realize that her “animation goggles” were not as unique as I thought. The evidence was everywhere. Whenever anyone criticized Bill Plympton’s tendency to time animation on 8s, they were seeing his work through “animation goggles,” judging his films by some universal standard that animation is supposed to follow. How dare Bill do artistic and successful work while thumbing his nose at the exacting standards and rules laid down in the golden age of animation! Recent comments posted by animation folks on various blogs discussing the Oscar-nominated The Illusionist also show the bias of “animation goggles,” especially in how some are flat out rejecting The Illusionist because it’s a serious film, not the feel-good “cartoon” they expect the animated feature to be.

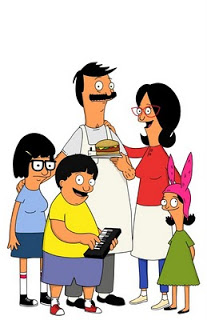

Recently creator Loren Bouchard’s series Bob’s Burgers (pictured below) debuted on Fox. As you may know, I was the lead animator and supervisor of the NY crew (Dale Clowdis, Dayna Gonzalez, and Hilda Karadsheh) that made the pilot on which the series was based. On the premiere of the new series, Cartoonbrew featured a talkback on which readers could comment their feelings about the show. There were many negative comments based on design alone.  It reminded me of the criticism that surrounded the look of The Simpsons when that series debuted in 1989. I don’t presume that everyone should love everything or that we all have to agree on the aesthetics of a show’s animation design, but I do propose that to dismiss a series based on this one criteria is to completely miss the point.

It reminded me of the criticism that surrounded the look of The Simpsons when that series debuted in 1989. I don’t presume that everyone should love everything or that we all have to agree on the aesthetics of a show’s animation design, but I do propose that to dismiss a series based on this one criteria is to completely miss the point.

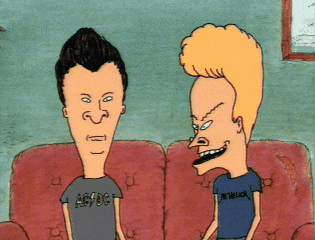

How should The Simpsons have looked? TV animation is a script-based medium. The Simpsons, South Park, and Beavis and Butt-Head (to name three successful animated TV series of the last twenty years), rewrote the rule book on TV animation––from writing, to satire, to social commentary, to graphic styling. But, that was hard to notice while wearing “animation goggles” that held all animation to one outdated ideal.

With time, most would have a hard time imagining the above three series looking any other way, even if the styles were off-putting when we first saw them. That’s our problem as animation people. We are slaves to our history, to the very legacy and exacting standards of all the good work done before us. But we make a mistake of using all that against our selves, so that it clouds our judgement. Non-animation people don’t carry around that baggage.

With time, most would have a hard time imagining the above three series looking any other way, even if the styles were off-putting when we first saw them. That’s our problem as animation people. We are slaves to our history, to the very legacy and exacting standards of all the good work done before us. But we make a mistake of using all that against our selves, so that it clouds our judgement. Non-animation people don’t carry around that baggage.

In the Jan 28, 2011 issue of Entertainment Weekly, they called Bob’s Burgers and Archer two TV’s funniest shows. That’s a far cry from some of the feedback by Cartoonbrew readers who dismissed the new series at a glance. Entertainment Weekly evaluates an animated series against the rest of the TV landscape. In contrast, many animation artists evaluate a series based on how closely it adheres to the gospel of Bob Clampett.

Clampett deserves his place in history, but so does Matt Groening, Mike Judge, Matt Stone and Trey Parker. It’s important to study and learn from the past and stay connected to our roots, but it’s destructive to the growth of our art-form and industry to use all that rich history as a wall to shut out all other approaches. New artists and writers are going to continue to innovate either way, with our without us animation goggle-wearing artists recognizing their achievements. But, I can’t help but believe that being able to recognize innovation might coincide with the act of being able to innovate. *Crunch* (the sound of me stepping on my animation goggles).