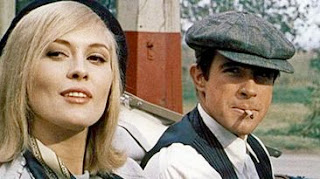

Stills from Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Stills from Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Forgive another post comparing an old live action movie to today’s animated features, but I am once again moved to do so. I recently caught a screening of Megamind, not because I was burning with curiosity nor was it because I had $12 burning a whole in my pocket. I happened to have a 3 hour gap between errands and teaching at NYU, so I figured, “What the heck.” I had no expectations going into the film. I’m not a “hurray for all things animated- guy.” But, I try to keep an open mind.

Megamind was okay at best. At times entertaining, but awfully forgettable. Sort of the definition of “meh.” All the characters were animated capably, but with that modern day, feelings on their sleeve method. We can trace this method of animation acting back to 90s era Disney, and I think this problem is just what Miyazaki is talking about when he said that Disney sets the bar too low. In short, viewers are not supposed to think anything on their own or be required to add their own humanity to the performance they see on the screen. So we get superficial attitude in place of nuanced acting. At Disney, this form of animation acting, calling it, “Name that Tune,” with the idea that every drawing is supposed to be a neon sign blaring the characters inner most feelings in the most cliched and over the top manner possible. Sure, that could be a fine approach to a specific character in a specific feature, but the way it applied across the board is a mistake.

The deepest most heartfelt moment of Megamind is (spoiler alert) when Tina Fey and Will Ferrell’s characters have a sort of parralell moment. They each visit the Metro Man museum to deal with their melancholy feelings. There’s lots of quiet and long scenes of them walking through the lonely cavernous space. While the sequence was heavy handed (this is super hero territory after all), it’s the films most moving moment. Yet, it’s ironic that it was achieved through layout and cinematography and not via character animation. Of course, there are many components in a film, all of which help tell the story. But, I couldn’t escape the fact that the filmmakers’ best conveyed emotion when their characters were barely on the screen.

Two weeks later I finally watched a film I had been meaning to see for years, a classic film from over 40 years ago, called Bonnie and Clyde. There’s a scene in the film that I’d like to talk about, one that goes against Disney’s “name that tune” school of drawing and everything that the modern era of animated features stands for. Bonnie and Clyde, played by Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, drive up to a a depressed backwoods gas station where actor Michael J. Pollard fills their tank with gas. Bonnie and Clyde spot a fellow conspirator in Pollard, and Dunaway seductively explains to the simple man that their car is stolen and that they’re bankrobbers. Pollard’s reaction to hearing all this is to twist and turn uncomfortably away and air punch at a gas station post. He’s sporting an uncomfortable grin and his glances back at Dunaway remind us of a little child. His reaction goes on for a long time––a unique reaction to the information he’s taking in. At the conclusion of the scene, Pollard robs his own cash register and donates the cash to his new partners in crime, just before jumping aboard their stolen car to ride away with them.

Now what boggles the mind is that animation can do anything. It can get into the soul of a character in a way that even a human actor cannot. Animation has its own properties of telling a story that are custom ready for an audience to engage with and project their own reality and life experience on, roughly to complete the experience. But, the audience can’t do this if the film follows the “name that tune” school of animation because such a technique makes the viewing experience a passive one. There’s nothing for the audience to think about on a deep meaningful level. Instead you get a sort of “animated fast food” experience. There’s nothing about full or traditional animation that requires going down this path. Dumbo’s sad and dazed expression as he walks to the water barrel with Timothy mouse (right after they visited Dumbo’s incarcerated mother) comes to mind. What about that is cliche? There’s so much sorrow in the little Elephant’s face. So much thought behind his eyes.

All of this begs the question of why such formulas (like “name that tune”) are being used in the first place. I see the value in getting the artist to conquer the blank page to dive in and draw, but at worst it encourages cliches in how it values instant readability above all else. If we are truly capturing the illusion of life, how is this form of instant readability compatible with that? Michael J. Pollard’s anguished reaction to being tempted by the romantic and exciting life of crime (or should I say, re-tempted, because his character’s backstory was that he had already spent some time in jail), would never pass mustard in the “name that tune” scenario. This is because it forsakes cliches, achieving humanity. And, while you could say that comparing animation to live action is comparing apples and oranges, there’s a lesson in here we’d be wise to learn and apply.