“Emotion, is the greatest special effect… it’s free and hard to do.”

At least that’s what Jorge Gutiérrez says, the director of Son of Jaguar, a new Virtual Reality short for Google Spotlight Story. The character designer, a Golden Globe nominee for The Book of Life, was one of several animators on hand to discuss a new art form with kids, at the New York International Children’s Film Festival. It was a brisk Mar. 4th Sunday afternoon at the School of Visual Arts theatre, and many kids were lining up at the microphone to ask their virtual-reality questions (technically, Gutiérrez was Skyping in). Also on the bill (in person!) were Pete Billington, director of Wolves in the Walls (Fable Studios) and Jim Hundertmark and Andy Rowan Robinson (Framestore) creators of the Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them VR Experience.

“Virtual reality is like a ghost.”

When you enter Son of Jaguar, the audience (of one) is an invisible observer. In this story, a champion luchador (Mexican wrestler) returns to battle the nemesis who stole his leg, and teaches his young son the value of courage. But virtual reality is not just a film. There is a moment <<spoiler-alert>> in SOJ that breaks the 4th wall, and you literally become a ghost: a deceased relative of the main characters. Suddenly there is eye contact and conversation. “Be aware of where you’re from, but don’t let that define who you are,” says Gutiérrez, who also told us his own back story about growing up as a “macho man” in Tijuana.

In television, “we are spoiled; [the directors] tell you where and when to look… We turn to the past, the theatre,” and use lights and staging to draw the viewer’s eye. Son of Jaguar is 8 minutes long, but Gutiérrez says it feels more like 30 minutes of animation. If a character gets thrown off screen, you still have to animate him landing, getting up, and walking back, in order to provide an entire environment. You have the main story, vs the wife’s story, vs the child’s story. You wind up with an audience who have different experiences and multiple points of view.

One of the children in attendance pointed out the Son of Jaguar’s particular “polygonal” character design. The titular Son is more chest than man, a hulking blocky pair of biceps and pecs, balancing on one tiny leg and one tiny peg leg. Gutiérrez called it a throwback to early 1990’s video-games, and offered another, rather ridiculous, explanation. The father (whose wrestling name is Son of Jaguar) is poor, so maybe “he can’t afford smooth surfaces… but the wife comes from a rich family,” so she has a smooth face but poor pixelated clothes. Gutiérrez’s Skype call was punctuated by a Power-point presentation of character design sketches, and he described teaming up with his wife. They made a cute team: he handled the macho characters, while she drew anything adorable or delicate.

Up next, Wolves in the Walls (directed by Pete Billington) is the third V.R. project for Fable Studios, but it’s their first to include V.R. hands! The experience is based off of fantasy author Neil Gaiman’s book The Wolves in the Walls, illustrated by Dave McKean. A little girl named Lucy is CONVINCED that wolves are living in the walls of her house. Lucy draws you into her world, literally, as an imaginary friend made with a magic crayon, so that when you operate the V.R. controls your hands appear as cartoony outlines. Billington calls it a magical moment when you first take an object from a character; an object such as the tin-can-phone you use to listen to the walls.

“We have 100 years of cinematography to draw on, but how does that apply to V.R.?”

Billington says there are no big camera moves in WITW, no cuts, but while we can’t control the camera, we can control the environment. When you enter the world, you are shrunk or scaled to Lucy’s size. Creating literal changes in size of the space you are in, creates an “emotional point of view, an emotional cinematography.” When Lucy finds her father playing tuba in his study, the room turns into a vast operatic space. Then it shrinks back down to bring the father and daughter closer together. It is the difference between changing your camera lens, and ‘incepting’ your reality.

On the big screen you need big body language. But in V.R., Lucy is close at arm’s length, in your face. You need a more natural and intense form of acting, and you ‘feel the space with the character near you.’ Billington showed sketches of Lucy’s facial expressions, describing how to avoid the “Uncanny Valley” while sticking to the original illustrations and maintaining a consistent level of cartoony-ness across the facial features. 10-15 people animated Lucy, with one 8-year-old voice-over actor and a young woman providing motion-capture. Using rudimentary built in Artificial Intelligence, Lucy can play tic tac toe. She knows when you are cheating, or not playing, and she can even gloat, reacting to the game play.

How do you balance interactivity and story? Fable Studios decided that any item you could interact with, such as a flashlight, pencil, sticky note or Polaroid, would directly help Lucy. You are the companion character in this story. When Lucy offers you a magnifying glass, her eyes flicker and she nods knowingly, waiting for you to take it: but there are 4-5 different actions she could take depending on your reaction. Billington pressed us to rethink virtual reality. What is unique about this medium? What can we NOT do in a film or in a video-game? In video-games, you are “gating” the story: unlocking certain achievements to advance the plot. There is none of this in WITW; if you do nothing, the story just advances in a slightly different way.

How does the viewer know what to do? Illusionism is used to direct the eye, like a magician leading with his hands. The writers have to predict the viewer’s reaction and guide them through dialogue and body language. After scripting, emotional pacing is set with a radio play, which then leads to to a “grey box” rough assembly, with crude animation and no real set (altho animators have been known to create their own choreography around cardboard boxes). Backstory is told through the environment rather than monologue. You learn about Lucy’s parents’ lives through the set dressing and objects found in the attic. This is Chapter One of Wolves in the Walls, where you can hear the parents’ voices through the walls. You won’t really get to meet them till Chapter 2 and <<spoiler alert>> the wolves come out in Chapter Three!

Billington revealed that Fable Studios is able to collect data on the viewer’s V.R. decisions (it’s unclear if this data is put onto a cloud server). I believe the question-asker was thinking about the design process, and how the studios researched its interactivity experience in order to create a better story. We learned that the photos, drawings, and notes you create inside WITW can impact the plot later on, and that we get to sign our name to the credits, because we really are part of the story.

Billington reminded us of the old “Choose Your Own Adventure” books, calling them a prototype of “branched narratives.” He describes Wolves in the Walls as a “twigging” narrative, which is one story with many tiny branches.

You have an impact on your environment, but the animators are still telling you a story.

Our final presenters, Jim Hundertmark and Andy Rowan Robinson of the studio Framestore, really broke things down for the kids. They went back to basics and explained key-frames and in-betweens, at 60 FPS, and the differences between cartoony and realistic styles of animation. They also demonstrated the importance of reference video. In the Fantastic Beasts And Where To Find Them VR Experience, every fantastical creature from the “Harry Potter” movie is on display, from major beasts, to ones that appear for only a few seconds. Since Framestore was already working on the movie, they had access to the original creature models and rigs, and just built the rest as necessary. The presenters would show us renderings of a creature, and then ask the kids to identify them and guess what real animals were used as reference. Fortunately, the kids knew every single fantastic beast!

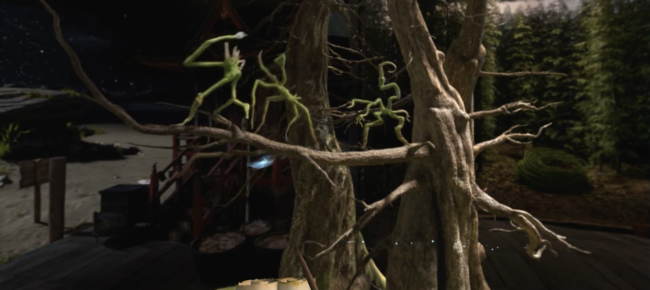

Did you know that the exotic Occamy (a feathered wyrm) is choranaptyxic? Meaning that it scales to fit the size of it’s environment? (A made-up word by J.K.Rowling, but perhaps it will get actual use in the V.R. industry). Framestore decided to blow up the Occamy into a giant, as big as they could get inside the experience, for maximum impact. The stick-insect like Bowtruckles’ movements were modeled after spiders… but not for long. J.K. Rowling never came to meet the animators but she did send thorough notes, and deemed the Bowtruckles too creepy for children. The presenters then explained how they used the concept of silhouetting in order to animate the fantastic little creatures, and pose their asymmetrical bodies in less scary ways.

NYICFF’s VR-JR Experience was inspiring to this ancient 30 year old, because now I have to learn how to talk about film… no, stories, in a whole new way. And filmmakers/storytellers have to rethink their whole approach and create a new vocabulary that combines movies with older and newer forms of entertainment. These enterprising animators consider Virtual Reality a triangular cross section of Film, Video Games, and Theatre (particularly immersive theatre, like Sleep No More).

“But in 10-15 years,” Pete Billington says, “we will NOT be talking this way anymore.”

Watch out! I think by then the kids in the audience will be graduating from college.

You can still catch amazing events at the New York International Children’s Film Festival, including the “Animators All Around” panel (featuring ) and “Girls Point of View” (stories here go way beyond fairy tales of girls!) ASIFA East members, check your past emails for discount codes!

AND GET READY FOR ASIFA ANIMATION FESTIVAL SCREENINGS!!!