Persistence of Vision

Review of Kevin Schreck’s new documentary, by Richard Gorey

There’s something so compelling about genius, to us mortals who might never achieve such dizzying heights. There’s something even more compelling about failure, which fascinates people in a very different way, as when we find ourselves slowing down to examine a wreck on the side of the freeway. Frightened by what we might see, we look anyway, don’t we— experiencing that contradictory mixture of “Thank God it wasn’t me,” and “Ooooo, just how bad was it?”

When genius and failure collide, the results can be unforgettable. That explosive mixture of brilliance and disaster, of promise and calamity, is on graphic display in a new documentary about director Richard Williams’ decades-long battle to make his Arabian Nights film The Thief and the Cobbler. Kevin Schreck’s new film, cleverly titled Persistence of Vision, is the most comprehensive examination yet of the story behind this epic fail, and of the artists who struggled mightily to realize Williams’ vision to create “the ultimate in animation”.

I’ve been aware of director Richard Williams’ Thief and the Cobbler project since the seventies, when as an aspiring cartoonist I read every animation article and book I could locate. In these printed pieces I saw stills and on television, occasional clips of the film. I was hooked: so excited to experience this magnificent and elaborate masterpiece, which, I was assured, would be released “very soon.” Then came the stories of delays and revisions, and years began to pass. Would the film ever be finished…and if it was, could it meet the expectations of people like me, who’d been promised a glorious and staggering epic?

Most animators and fans of the art form know the ending to the story: the film didn’t see theaters, at least not in the form Williams envisioned. That tragedy, which unfolded over decades, has become a part of animation history and legend: I know few professionals who haven’t seen the “Recobbled cut” of Williams’ epic online– and over the years I’ve met so many people who have strong opinions— positive and negative— about the project.

Kevin Schreck, a filmmaker and animation enthusiast, has done a terrific job of filling in the blanks, answering the unanswerable questions, and examining the trajectory of The Thief and the Cobbler in his documentary Persistence of Vision, which had its NY premiere at the SVA theater on Friday, November 9th. I corresponded with Kevin via email, and attended the screening, to gain more insight into this complex and troubling cautionary tale.

“Persistence of Vision” recounts the making (and unmaking) of director Richard Williams’ Arabian Nights epic

Schreck shared his journey with me, saying, “I wasn’t aware of [Cobbler] until about five years ago, when a friend showed me Garrett Gilchrist’s fan edit, the “Recobbled Cut.” I was blown away by the animation and level of detail. Right then, I thought this could make a fascinating subject for a documentary. But what held my attention was the fascinating story behind the making, and unmaking, of this extraordinary film. It’s really more of a character study of this phenomenal artist.”

Such a film would have to be. Projects as revolutionary and unique as The Thief and the Cobbler are often guided by a passionate personal vision… but the unfolding of that vision isn’t possible without the belief and cooperation of possibly dozens (or hundreds) of artists who devote their skills and lives to the dream. Who was Richard Williams, to the people who sacrificed and toiled to bring his vision to the screen? And how did they feel, after years of their lives had been spent, when the film was taken away from their director and completed by other, less skilled hands? Is the feature one of animation’s “lost masterpieces,” or is it a warning to those who might be driven by passion and ego in equal measures?

“It’s hard to say,” Kevin says. “I don’t know if you can accurately measure what makes something a masterpiece. But there are certainly elements of genius in what remains of Mr. Williams’ film, without a doubt. There are portions from his film that are stunning, and are hard to figure out how they were even accomplished, even for people who know a lot about animation. And to see that rare footage on the big screen is a real privilege. It was a real privilege to be able to speak with so many talented artists who were involved in this amazing piece of film history. Some people held Williams in very high regard, others were slightly bitter about their experience, and the majority felt a variety of differing emotions. But the one thing that was unanimous between everyone was that working with Mr. Williams at his studio was the most formative, influential part of their career.”

I experienced the same contradictions when I wrote an article about the making of Williams’ Raggedy Ann and Andy some years ago. My interview subjects were often guarded, and remained fiercely loyal to Williams. His legacy as a teacher and mentor will perhaps surpass his reputation as a film director of note, Roger Rabbit notwithstanding. Those who knew him and who worked with him admire his skills, work ethic, and enormous talent, even as they might disapprove of the man personally.

As an animator, Williams is a legitimate master, and some of his work has set a technical standard that will never be matched. But like many great talents, Williams seems to have suffered from tunnel vision— a quality, ironically, that is essential to making films, running studios, and motivating large teams. Some time ago I wondered about the corrosive personalities of such directors as James Cameron, and a friend said, “I don’t think you can make a film as big and as complex as Titanic and be a nice guy at the same time. I think to a certain degree people have to fear you, if you want to get anything that challenging completed.”

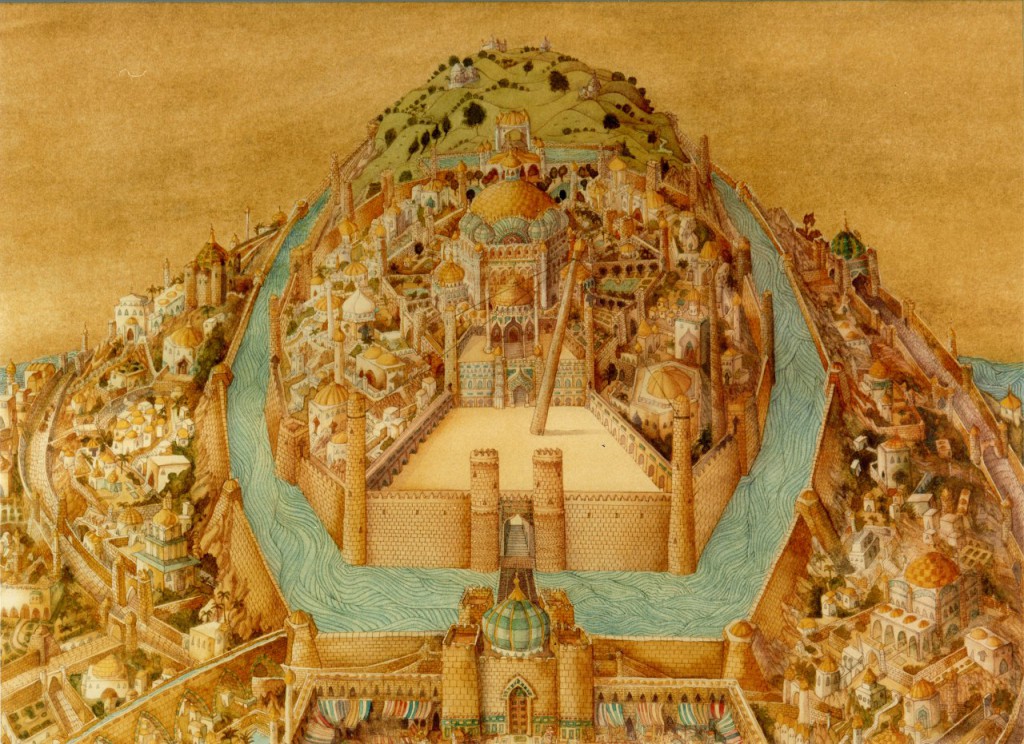

This stunningly elaborate art suggests the opulent vision Williams had for his film. What’s left of Williams’ dream is compelling and brilliant: the finished film would have been quite unlike anything previously seen in feature animation.

Did people fear Williams? I didn’t get that impression from Schreck’s excellent documentary, which was surprisingly balanced. This is a story that could easily have been told in tabloid fashion. It’s a soap opera with all the expected elements: betrayal, denial, money, skullduggery, and in the end, professional tragedy. Schreck is remorseless in his examination of the process, but he is very fair, even compassionate to Williams, whose decisions (and indecisions) contributed to the events that unfold in often excruciating detail in Persistence of Vision.

Schreck explains, “I don’t think my documentary functions as a sort of cautionary tale. My mission isn’t to say, ‘Don’t do anything creative or ambitious, because you’ll just get screwed in the end,’ or anything like that. I think it’s just my attempt to tell a unique story about a unique individual who had this real unique vision. I’m more interested in the conversation that my project aims to generate than supplying easy answers. There’s no omniscient, god-voice narrator in the film telling you how to feel. It’s up to the audience.”

This objectivity strengthens the film, and makes the experience an inclusive one for the audience, though it’s hard not to cringe when Williams says in his Oscar acceptance speech, “the best is yet to come!” Oh, if only that had been true! Williams has been famously recalcitrant in regards to discussing the aborted movie, perhaps understandably. Was it possible to include the director in the making of the film?

“Mr. Williams declined to participate in my project,” Kevin told me. “I can’t speak for him officially, of course, but I can only imagine that the experience must have been devastating. The vast majority of people that I reached out to back when I was developing this documentary were very supportive. They all respected Williams, but I also think they really felt that this was a story that was worth telling, and one that might slip away and be forgotten. My project is the first major work that attempts to tell this otherwise untold story of cinema history.”

It surprised me how many people even outside the animation industry knew the film (at least by reputation) and were aware of the misfortune that surrounded its creation and eventual destruction. Kevin spoke at the screening and told the audience about his reluctance to continue with the film, once it became clear Williams disapproved, and would not be participating.

Richard Williams devoted most of his life, and all of his considerable gifts as an animator, to the making of a film that might be his most lasting legacy, despite the troubles that surrounded it.

“I think Richard Williams’ impact on the art of animation cannot be overestimated. He trained hundreds of amazing artists, many of which are still working today. And that has a domino effect, influencing even more people, all around the globe,” Kevin says. “ I rarely say these things about people, but Williams is definitely one of those last great artists, a true master of his medium. He’s the Rembrandt of animation, I think.”

In this light, Kevin doubted whether or not telling this story might harm the director in some way, but his collaborators encouraged Schreck to soldier on, since, they argued, the story didn’t belong exclusively to Williams: it also was the legitimate property of the hundreds of artists who spent their talent and their happiness on the feature. These dedicated, loyal craftsmen and women needed to be heard, and their stories are involving.

The documentary addresses the Disney feature Aladdin, which many people feel borrowed heavily from Williams’ Arabian Nights epic. Kevin doesn’t believe such accusations serve the dialogue.

“It’s hard to make too many specific accusations. But Williams was working on his film over a quarter of a century, and he was quite aware that things could leak out and people might ‘borrow’ portions from it. I don’t think there was any malicious intent behind it. I guess you could call it a form of flattery. But even if there was no direct plagiarism, it’s still a bad situation to have a movie with similar elements be released at about the same time as yours.”

In light of the astonishing success of the Disney film, what then, is the legacy of Williams’ truncated masterpiece? So many people think they “know” the film, but so few have seen it, or have experienced it as the director intended. Does it have a right to a place in the history of animation, now that the computer has redefined “state of the art”? Williams was, in the words of master animator Art Babbit, “trying to save the art of animation, for future generations.” Was that necessary?

“There’s no melodramatic, rousing speech to the audience about how we must save the lost art of hand-drawn animation, but people who have seen my project — even those that didn’t have much of an interest in animation before — seemed very impressed, and even emotionally touched, by just how unique and authentic Williams’ animation is in the film,” Kevin says. “There’s such a tactile quality to that art form. …You can really sense the presence of the artist. CGI is amazing, but it’s a bit too slick and polished, in my opinion. It can’t really replace the feelings that traditional forms of animation can inspire in a viewer. But I think there’s a place for every kind of animation. None of them are necessarily better or worse than any other. It’s like comparing painting and sculpture.”

Persistence of Vision is a tight, elegant, and thorough examination of the production process, but it also presents an opportunity to see the pencil tests and final color tests from The Thief and the Cobbler on the big screen. These sequences were met with delight and appreciation from the NY audience, who were quiet and respectful, except for the occasional groans of despair or embarrassment that occasionally echoed through the auditorium. Sometimes the documentary is a painful experience, but it’s always informative and even-handed. It would be easy to “blame” Richard Williams for everything that went wrong with his feature film. He is often his own worst enemy, but watching his boundless enthusiasm in these archival interviews, it’s hard not to want to see him succeed, and that’s why the film is so occasionally uncomfortable: we already know the ending. We watch, fascinated, as Williams ages before our eyes, and we see this eager young artist become more and more tired, discouraged, and wary of those around him. The film is of course as much about Williams’ journey into the “heart of darkness” as it is about the eventual failure of the project. Both dramas are equally intense, and both are explored in depth.

At one time, about seven years ago, I recall seeing an article that promised the Disney organization would “restore” Williams’ film, and give it a limited release. So far, that hasn’t happened.

Kevin agrees: “I don’t think The Thief and the Cobbler will ever have an official restoration, to be honest, for various reasons. If you want to see the film in the most presentable version, I would highly recommend Garrett Gilchrist’s ‘Recobbled Cut.’ My project wouldn’t have been possible without his tremendous work, and his fan edit is the most faithful (and bearable) version out there of Williams’ vision. I don’t know what sort of impact my movie might have.”

Will Persistence of Vision trigger renewed interest in The Thief and the Cobbler?

“I’m not expecting anything revolutionary,” Kevin says. “At the end of the day, I just wanted to tell a good story. And so far, a lot of people seem to be enjoying it. That’s more than what I ever asked for already, and it’s a real honor.”

Persistence of Vision is a rarity: it’s a documentary about a single animated feature, and there aren’t too many of those. Then again, there aren’t very many animated features worthy of special treatment. That The Thief and the Cobbler (a film that wasn’t even completed) merits this kind of attention and scrutiny is evidence of the impact Richard Williams continues to have on an industry and an art form that in the end betrayed him.

This is a thoughtful perspective on the conflicted emotions we all have when watching this film. It’s full of highs and lows, and when someone asked me what I thought after seeing the film, I replied that it was sad. I can see how much he touched and changed the lives of many when they were working on the film. How much they must have learned from him over the years. There was a collective embarrassment in the room when he spoke of how flexible animation is and the ability to change anything you want. That flexibility makes animation wonderfully unique but it can also be its achilles heal. I’ve been on quite a few projects that never saw the light of day due to a creator’s inability to let go. Mixed emotions here.

Nice review and article, thanks for posting this.

We were not able to make the screening and this review makes me sorry for it. Mr. Gorey has nicely outlined the overall project, what the filmmaker was trying to achieve, and the audience’s reaction. He puts the documentary into perspective and I look forward to the chance of catching it in some other venue. Thanks for that.