Culhane in 1983

John Culhane had a way of teaching History of Animation that made animation the least important part of his class. He showed us clips of the Berlin Wall coming down as a general blew a war whistle to herald an age of peace. He showed classic movie clips about soldiers reuniting with their families. He insisted we call Dr. Seuss’s Grinch the “Gruch,” so as to remember the acronym for Gradation, Repetition, Unity, Contrast, and Harmony – the five elements present in all art. His orbited the class around Baruch Spinoza’s 38 emotions, and related how at Expo 67, Disney legend Art Babbitt told him of the 39th – Risibility, the emotion you feel when you laugh.

I met John Culhane in the fall of 2001 (he refused to be called “Professor,” unless it was in the voice of Ludwig Von Drake). He was one of the reasons I chose NYU to study animation. I was sitting in the back of the class that Wednesday night, trying to be inconspicuous. John asked a question to the class, “Who is really responsible for drawing the first animation of Mickey Mouse?” Finally I raised my hand and said, “Ub Iwerks.” John lit up. “Young man, what’s your name?” “Jake Friedman,” I said. “Jake Friedman,” he exclaimed, “you are on your way to the top!”

I met John Culhane in the fall of 2001 (he refused to be called “Professor,” unless it was in the voice of Ludwig Von Drake). He was one of the reasons I chose NYU to study animation. I was sitting in the back of the class that Wednesday night, trying to be inconspicuous. John asked a question to the class, “Who is really responsible for drawing the first animation of Mickey Mouse?” Finally I raised my hand and said, “Ub Iwerks.” John lit up. “Young man, what’s your name?” “Jake Friedman,” I said. “Jake Friedman,” he exclaimed, “you are on your way to the top!”

John’s idea of taking roll took at least half of class time. Every student inspired some anecdotal riff. He’d ask for each person’s hometown, and every location triggered for John a moment of joy. A student named T. J. was from Baltimore, and John insisted on calling him “Baltimore T.J.” Without fail, if someone said they were from Allentown, PA, John would gasp, “ALLENTOOWWN??!!!” after a movie-musical line. He would smile so wide that his cheeks covered his eyes. Even if we didn’t get the joke, it was hard not to join in on his exultation. In a room of college-age dilettantes, he was the youngest soul amongst us.

And still, John was not afraid to talk about the saddest aspects of human nature. My first class with him came on the heels of 9/11. He relayed stories about first responders, and shared in our grief and pain. He often talked of his wife, Hind’s work empowering Middle-Eastern women. As close as he was to laughter, John was never far from tears. He could access his emotions with child-like ease – a trait perfect for an animation class.

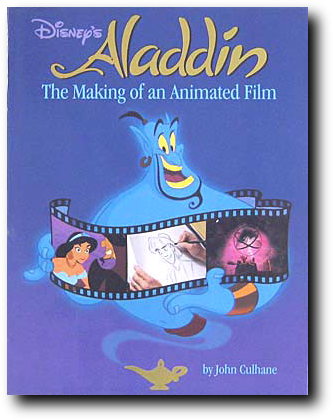

It’s no secret that John loved all things Disney. I learned his name in 1993 when I was given a copy of Aladdin: the Making of an Animated Film. I dissected that book cover to cover, leaving it highlighted and filled with liner notes. My favorite part was its introduction in which John recounts meeting Walt. Later that decade, I watched John in the documentary Frank and Ollie. On film he was enthusiastic, expressive, and ebullient. That’s why I signed up for his class in 2001.

John’s class was offered only in the fall, but I volunteered to be his TA for two more years. I wrangled laser discs and video tapes on Will Vinton, the Brothers Quay, Winsor McCay, the Hubleys, and UPA. Mostly, John lugged his video library with him in a couple rolling suitcases plus a carry-on. He would write the information of each animation clip on the chalkboard – name, director, year, and country – even after the board was full of scribbles. You could take notes or just draw – if Glen Keane could doodle during one of his lectures, so could we. We discussed how “Gerald McBoing Boing” is really a sad little short devoid of a loving touch – an aspect I integrated in my senior thesis film. It was in his class that I watched what was to be one of my favorite animated films, “Life in a Tin,” by Bruno Bozzetto. When John saw it at Expo ’67, all the old-timer animators gave young Bozzetto a standing ovation. John couldn’t stop talking about the film’s Butterfly World– a colorful paradise that only appears when a person is in childhood, in love, and then in the grave.

These last several days I’ve been watching the outpouring of grief over John’s passing. The industry at large is mourning – a testimony to the reach of this man. His connections in the classroom are burned into my memory. One October he dedicated a day to Disney animator Ollie Johnston, and asked each student to write a letter of appreciation to Ollie, listing their favorite Ollie scenes. The next week John played a grateful voicemail that Ollie left for us all. Other days we would be treated to amazing guest speakers, like animation vets Dave Bossert or Bill Frake, or even his son Michael to present George Dunning’s Yellow Submarine. After I graduated NYU, I was honored to be one of John’s guest speakers. On my last visit, John announced to the class – and to me – that I would be writing the biography of Art Babbitt. And I have been.

Walt Disney told John how to become a professional in whatever you love, no matter what the artform: start doing it for your friends and family, and slowly keep widening your circle. John shared this advice with his class every year. I took his words to heart, and became a writer for the aNYmator newsletter, and then for Animation Magazine. Like John, I started by interviewing industry professionals and asking about their craft. And like John, I reveled in the chance to be a fan and a mouthpiece at the same time. I’m grateful I was able to pay him tribute with separate thanks in my book, The Art of Blue Sky Studios.

I always took my inner Animation Historian spark for granted. But John saw it. He knew it the day I met him in that classroom. If you were his student, your first assignment was to fill out an index card with information about yourself. He never returned these cards – he wanted to keep proof that he knew us once we became famous (he missed his chance to ask Tim Burton for one).

He saw greatness in all of us. And he saw the best in our world. His class was called “History of Animation,” but it was really a lesson on how to live a life of joy. He was the perfect teacher, and a wonderful friend. Thank you, John.