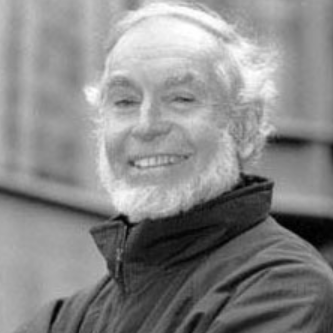

Animator, father, devoted husband and partner, historian, writer, and friend, Howard Beckerman touched the lives of so many for so long that no words can encapsulate the love felt for him as news of his passing travels throughout the animation community and the world. Howard Beckerman may not be a household name, but without exaggeration he earned a place in animation history next to the greats. His influence and example live on in his writing and films, and in the hearts and wrists of the thousands of aspiring animators he taught and mentored over course of his seventy-five year career in animation.

Howard set an indelible example of humor and human kindness to anyone with whom he crossed paths—a quality that has sadly become rarer in today’s world. He was not a boastful man. Rather, Howard was charming, thoughtful, and deliberate. He possessed one of the most encyclopedic minds on animation and its history—a mind that remained tack-sharp even as his body began to give out. He was an observer who translated a lifetime of empathetic observation into a style free of outward sarcasm or bitterness. One can see this kindness in his line, which seems to dance effortlessly and freely…without judgment.

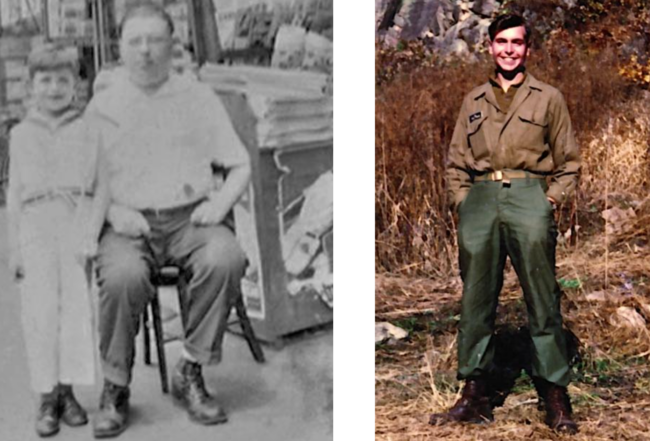

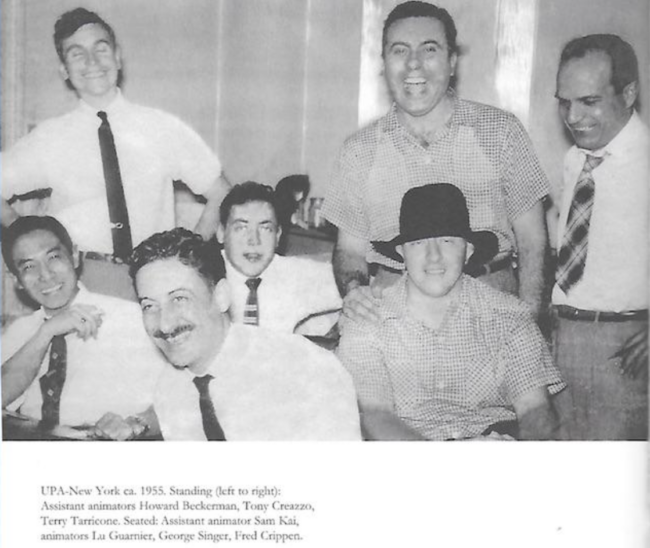

Howard Beckerman was born in Brooklyn in 1930. His older sister took him to see Pinocchio when he was a young boy and the film inspired the young Beckerman to pursue cartooning and animation. He attended the High School of Industrial Art and began working for Terrytoons in 1949. Howard served in Korea, and found himself close to the front lines working for the signal corps, which eventually brought him back to New York where he finished his time in the service making training films. Afterwards, Howard resumed his work in commercial animation in New York both as an animator and story artist. After spending time at UPA and various other studios, Howard and his wife, Iris, opened their own animation studio in 1970 on the advice of friend and colleague, Tee Collins.

In the 1970s, animation schools did not exist. But with the advent of new formats such as super 8 film, interest grew and colleges began ramping up their offerings. Howard began teaching animation at the New School, building a program from scratch. From there, he taught animation classes around the city between taking freelance animation jobs, eventually becoming a fixture at the School of Visual Arts where he taught for forty years.

Howard seemed to know or have met everyone, from Hans Richter to Evelyn Lambart. He wrote for many of the animation and film magazines of his time such as Millimeter and Making Films in New York. He was a regular contributor to TOP CEL, IATSE Local 841’s monthly newsletter and remained active with ASIFA East for decades, serving as the organization’s international liaison. His work with ASIFA as well as his output of charming films allowed him to travel the world to attend festivals, serving as one of New York’s most effective ambassadors for animation and earning him the unofficial title as ‘Dean of New York Animation.’ He taught all aspects of animation, but may be most remembered for developing and teaching some of the earliest for-credit college level History of Animation courses in the world along with John Culhane and Leonard Maltin. In 2001, his book Animation: The Whole Story, reached the shelves, providing insight and advice to a generation of aspiring animators.

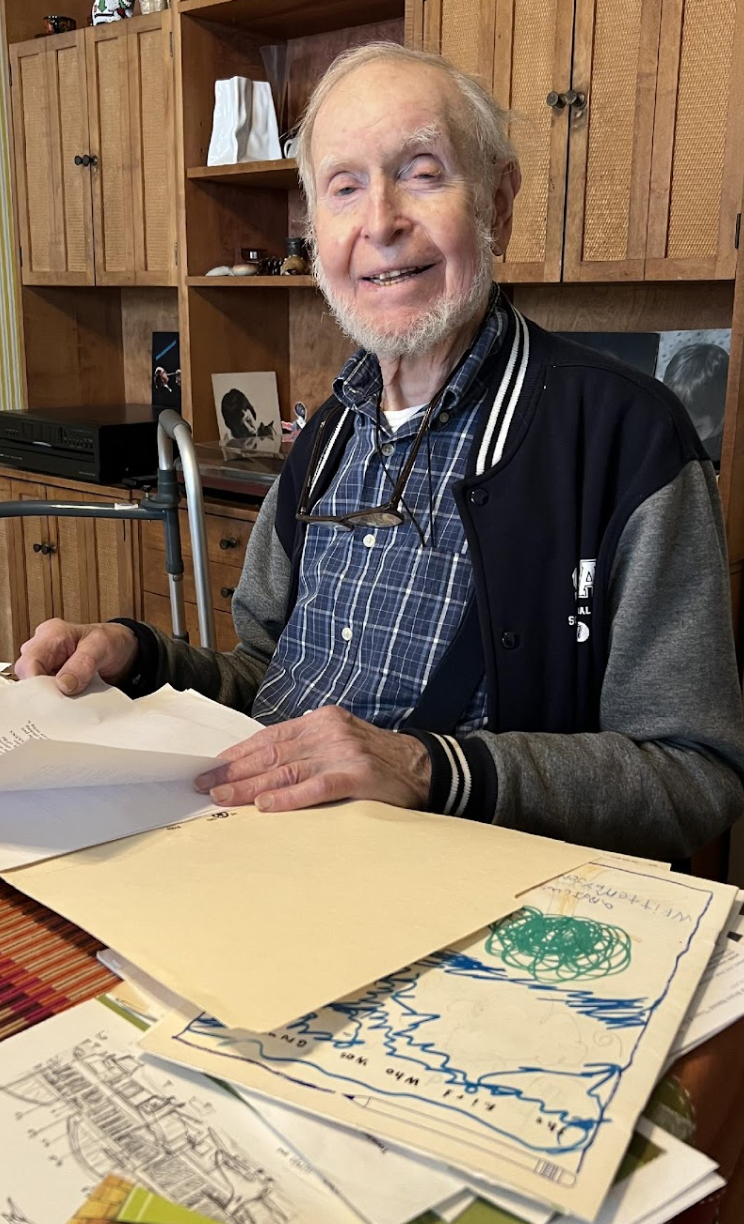

Howard Beckerman straddled a significant period in animation history, beginning during a time where his contemporary, Izzy Klein, could still recall being in a room with Winsor McCay to the current industry dominated by digital methods and techniques. Howard had an expressed preference for hand-drawn techniques, and was dissatisfied by what he considered the formulaic and homogenous approaches to computer animation. But in his last months, he delighted in creating simple animations on his iPad, remarking with a huge smile at the wonder of its possibilities.

While the animation community absorbs the magnitude of the loss, it’s important to remember the ways which Howard lives on. He set an example for a certain kind of empathetic approach to being, a kindness, and a sense of humor. To those who knew Howard, he will always live in our hearts. To those who never met Howard, its perhaps helpful to read his own words, written in 1966 after the death of Walt Disney, as they are equally as fitting to him—an unintended yet equally fitting metaphor perhaps to his own remembrance. He wrote:

“I never knew Walt Disney. However I saw him once, many years ago, walking along Madison Avenue. I remember noticing at the time how numerous were the shop windows that he passed which afforded the likenesses of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck on such items as books, watches, toys, and clothing. This man had succeeded in weaving a spell over the whole world, a spell that brought pleasure to everyone and fame and riches to himself.

To those who knew Walt Disney and were able to take their meetings with him for granted, it might seem strange for someone else to make so much of the fleeting moment.

The explanation surely lies in a fact: that fact that many of us grew up during a time of economic depression and world war, a time of very little magic. How wonderful a moment it was then for one, now grown up, to watch a gray-haired man with a mustache, recede into the distance along a New York street and be thankful for the magic that he had given us all.”

Thank you, Howard.