by Robby Gilbert

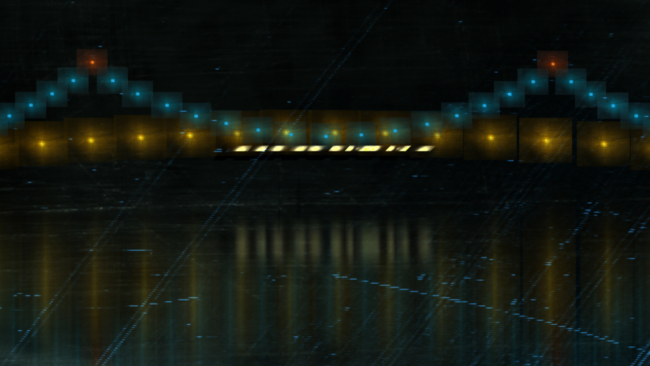

John Morena is the quintessential New York independent animator. Born and raised in the Bronx and currently working out of Brooklyn, he finds inspiration in the everyday goings on of the city and synthesizes the quotidian into picture and sound. “New York City is full of surprises,” notes John. “It’s brash. It’s in your face. The city has a way of providing a straight path to the truth that naturally flows into my work.”

John’s work found its way into the festival circuit in the 2018 / 2019 season— including Annecy, Ottawa, Hiroshima, and Zagreb. He’s a big name that you may have yet to hear of, but I suggest keeping your ears open. His thought provoking and expressive short films (most hover around one minute in length) are a feast for the senses and are like nutritious film snacks. In fact, Morena compares his work to being given grapes at Halloween instead of candy…they come in bunches, they’re lush, juicy, snackable, and probably not what you came to the door expecting. His films are, nevertheless, both trick and a real treat.

I sat down with John recently via zoom to discuss his process, ideas, and animation worldview, and came away impressed by his realistic—if somewhat healthily nihilistic—approach to animation that brings much to the discussion of animation as an artform, and as a business.

So, John, thanks again for taking the time to chat. Your work is so expressive and almost musical. In fact, you credit yourself at the end of your films as responsible for both picture and sound. Can you talk about why this might be?

Most indie animators take on a lot of the roles required to make a film. When you say you’re a director or say that you’re an animator, it doesn’t really cover all that you do. In my case, 90% of the time I fill all of the roles. So I credit myself as ‘Picture & Sound’ as a sort of shorthand. It would be embarrassing to credit just myself in each individual role. So “Picture & Sound” very broadly covers it and if it’s the only credit with my name attached then I think the audience is safe to assume I’m also the director.

Gotcha. I think that that’s an interesting point, because the word animation often conjures up something different for everyone—but by and large, it’s cartoons.

If you tell someone you’re an animator, generally they’ll envision you sitting at a desk drawing pictures and only doing that one thing. Whereas in my case – and I think in most independent animators’ cases – we’re all doing much more than just that for our films.

I think that’s a frustration for me because when I look at work like yours I am really inspired by it. Here’s an artist really pushing the boundaries of the form in a way that I wish was more popular, I guess… for lack of a better descriptor.

I appreciate that. Thank you. I’m only loosely setting out to do “something different”. It’s not my motto or anything. Hard and fast tenets like this can be limiting in a bad way.

As far as it being more popular, yeah I think we all want that. However, I feel like the general audience’s relationship to animation in the United States is a very anemic one. Animation, in the mind of the general audience, is whatever the major studios tell them it is. And that’s where the buck stops. This idea is only reinforced by major studio leadership and it can be harmful to the enterprise of independent animators and their morale.

For example, at the 2022 Oscars, Disney sent out the actresses that played three of the princesses in their respective live-action remakes to present the award for Best Animated Feature. Now these are official, paid, Disney representatives that said, out loud, to an audience of roughly 20 million television viewers – and a room full of high level producers, investors and powerful industry people – that animation is exclusively a children’s art form. That it’s meant for children to watch “over and over and over and over and over” ad nauseum. It’s for adults to have to suffer through because, of course, they aren’t children. So, naturally by default, they’ve grown out of it. Then in an attempt to be cheeky they go, “I see some parents out there know exactly what we’re talking about.”

Make no mistake, words like these are the result of money spent on market research. This is a carefully constructed official word from the company itself. On the network they own. Can you imagine the zoom calls coordinating this PR speech like it was a good idea?

Another example: the president of another major animation studio was interviewed as part of Annecy’s Expert Insights video series. They were asked what, in their opinion, was the biggest problem facing animation today. They cited “over-saturation” as the big problem. Too many films being made. They were then asked how this could be fixed. They said, and I quote, “Films have to be good now. You can’t make a mediocre film anymore and expect people to go see it.”

You know…stuff like this is just plain insulting and belittling. Films have to be good now? Don Hertzfeldt isn’t good? David OReilly isn’t good? Julia Pott isn’t good? Kirsten Lepore isn’t good? Remarks like these are proof that the gap between industrial-strength animation and independent animation is a world apart. These companies are so gigantic, their heads are above the clouds. So when they look straight ahead all they see are other giants. They look down and only see clouds obscuring everything happening below. So they don’t even see us down here, therefore we must be lesser. Must be irrelevant.

I wish it was different but also GFY, you know? The entire reason why American audiences are cinematically undernourished is because of the business-only attitude of behemoth mainstream studios. I think that in the United States, we are probably the least equipped to properly view any films that are not mainstream. Not just animation, all world cinema.

Why is that?

More and more, audiences are generally shown the same kind of thing in a redundancy. Not all films and TV shows of course, but most of them being released have that safe and homogenized aroma to it. Many rehashes, redos, remakes and retellings continue to be made and audiences don’t seem to be fatigued by them at all. So naturally, more are produced.

Other things like: there absolutely has to be dialogue in a film in order for it to matter. Hard to imagine selecting a show or film on a streaming service with no talking in it, right? And that dialogue also must be in English. Try getting a general American audience member to watch something with subtitles. Maybe just a few out of ten might be open to the idea but in a climate where a large portion of information is delivered with dialogue in movies and TV, audiences will have to recondition themselves to read while watching. It’s for this reason why some folks will never see a Kurosawa film. Never see a Jean-Luc Godard film. No Fellini. It’s tragic. Just makes me sad to think about.

There is a short animated film by Frank Abney called Canvas. It has no dialogue but it was on Netflix. I think it still might be. Anyway, during the pandemic this film got a lot of support on social media. You would see people post about it and say ‘this isn’t getting enough attention. People should be watching this. Go support black filmmakers”, etc. Beautiful stuff. But you read some comment sections about this film and some people will say “this was good, but how come there wasn’t any talking”. Or “boring, no dialogue.” I’m sure wonderful things have happened for Frank Abney since, but my broader point is: imagine your film finally breaking through to a larger audience and their response is “where’s the talking?”

It all equates to what I said before: the gap is wide. Studios are mainly interested in their bottom line so they’re naturally going to make stuff that keeps making money. But capitalizing on an IP and making a great film should be a more cohesive marriage in mainstream animation. For instance, Spider Man Across the Spiderverse is a great film. But you don’t set out to make Spider Man Across the Spiderverse because you’ve got something to say. You set out to make a film like that because you’ve got toys and oven mitts to sell. The humanity is added afterwards. The performance of the IP across all possible business sectors is the core impetus for all of the mainstream stuff that audiences go gaga over. The film itself is just one part of the pie.

What led you down the experimental animation path?

Well, when you grow up in a place like where I grew up in the Bronx, which is very Italian-American, blue collar, a lot of union workers, city workers, stuff like that. There are not too many real life examples of people being animators. If someone did video work, it usually meant that they were a professional videographer for Weddings and Sweet 16 parties. I did have a family member who was an illustrator that the family referred to as a “commercial artist”. So I guess there was that but it wasn’t like anyone said “hey look you could be that too.”

So not really knowing which way to go, my first step was to go to school for illustration. Originally, I went to UConn and was there for two years. I had an epiphany in my first year at UConn that I wanted to make movies. But I also wanted to keep drawing. So animation just made logical sense and I sort of fell into it by necessity. After two years in Connecticut, I came back to NYC, went to CCNY for a year, then went to SVA. I had an experimental class at SVA with George Griffin that was influential, among other key moments there. Here was a real live person who was already doing it and was respected and accomplished.

I’ve also always been interested in movies outside of the mainstream. Really shitty B-movie stuff and weird animation. My stepfather introduced me to Ralph Bakshi and Ed Wood films. I think all of this led to an interest in unorthodox approaches. I liked to use unorthodox techniques in my visual effects work when I was doing that kind of stuff a lot. I felt, for better or for worse, it made my work unique.

It’s probably an obvious question, but what does New York specifically bring to your artwork or process?

Well, this place is full of surprises. Because I grew up here, that naturally influences my work and I like to welcome surprises and allow them a chance to assimilate into my work.

New Yorkers, especially native New Yorkers, have a reputation for being in your face and boldly honest. Sometimes brutally honest. All of that naturally flows into my work. Again, for better or for worse. It makes me unafraid to create unpolished art. It’s ok to be sloppy. There’s beauty in the grime.

I really loved your film, Home: A Portrait of New York City. Really, really cool. I haven’t quite absorbed it fully yet, and I’m not quite sure if I’ve articulated a question about it, but, who are some of your influences?

Thanks for the kind words! Whenever I’m asked about my influences, I draw a blank with specific ones lol. Inspiration comes from so many directions and when you least expect it. Not just film. Not just animation. Not just music. Not just museums. Not just the outside world. There is inspiration in all things.

I love Francis Coppola and his bravery. The raw power of Scorcese’s and Kubrick’s films have always influenced me. As I got older, John Cassavetes became an inspiration. Suzan Pitt and Jan Svankmajer are animators that inspire me. They are so uniquely and honestly themselves and their films connect to us in such a primal way. They’re both geniuses and very brave. I guess I gravitate towards brave artists.

Let’s talk about music and art and animation.

I think The Beatles were brave. They were always innovating. Yellow Submarine has its place in the pantheon of great animated films for good reason and not just for the music.

Frank Zappa. Sonic Youth. Nirvana too. I thought In Utero was a very brave and bold follow up to Nevermind since it went in such a radical, art-noise direction, despite what their label wanted or what their fans thought they wanted. The lesson there is true artists stand by their work no matter what.

Billie Eilish inspires me too because of the DIY nature of that great album her and her brother made. Another music artist named Caroline Rose inspires me as well. Her last record, The Art of Forgetting, is an inspiration. Very brave.

I like when music artists record their records in a way that you wouldn’t have learned in a technical school. They’re letting the creativity inform how they do the technical side, not the other way around. I utilize this approach almost entirely in my film work. The way the film feels is paramount. Everything else is second.

So you’re also a musician?

I wouldn’t say I’m a musician, but I dabble with guitar and piano. I had a MicroKorg synth a few years ago that I liked messing around with. I have a Stylophone too. Sometimes I like to record my own stuff but I’m more interested in experimenting with making sounds, not necessarily making music.

The term, visual music comes to my mind when I see some of your films, like Home: New York film. For me, you’re tapping into a very musical area of visuality. And some of my favorite animators are on that line, where there’s sort of this melding of the two practices.

Whether it’s conscious or not, you’re seeing this animation art form kind of a synthesis rather than an objective entity.

Oh, definitely. As they say, sound is half the picture. It’s corny but it’s true. If you have bad sound or if you treated the audio portion as an afterthought, you’re robbing yourself of the power of sound.

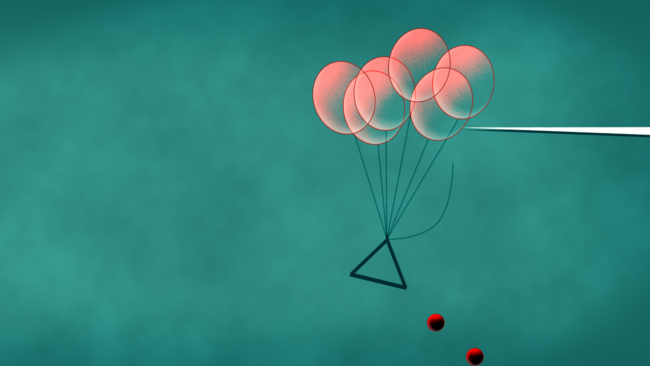

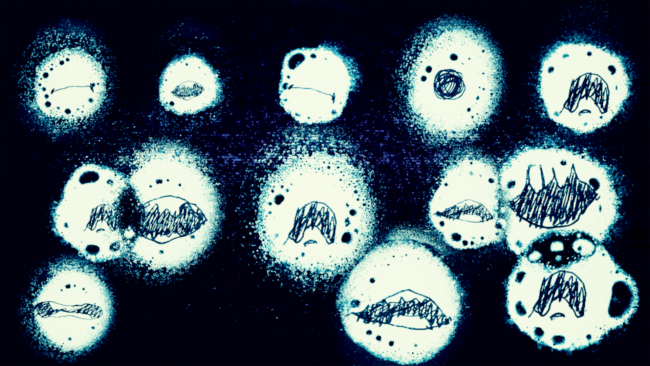

I made a film called String of Sound. The entire idea came from a walk back home from the coffee shop. The people that I passed on the sidewalk were either coughing or laughing or making other non-language mouth noises. It dawned on me, if I was in Indonesia or something, or any place where I didn’t speak the language, I would still understand these sounds. So, what are all those kinds of sounds? Then I made a film about it. A lot of my films originate this way, with sound ideas.

Filmmakers should consider and integrate audio ideas more often, in my opinion. Really, the whole spectrum of disciplines. Like, how to do everything— to get your hands into doing all the things. It makes you a better director if you’ve walked in the same shoes of the people you are directing.

Since your films are so out of the ‘mainstream,’ have you gotten any negative feedback?

Not really negative but a very prestigious festival in France that is only for short films that said my films were too short. Too short for the short film festival! LOL. I thought that was pretty funny. A Seinfeld moment. Those Area 52 films weren’t initially designed for a theatrical setting or to be played on television though so…whatever.

Where do you see them being played? On YouTube?

Well, the platform for Area 52 was Instagram. The time length of my films, those limitations were totally dictated by Instagram, because I was only ever gonna show them there. This was at a time when video on social media was not nearly as prevalent as it is now. Back then (in 2016) they had just raised the time limit of videos you can upload from 15 seconds to 60 seconds. So that’s why the Area 52 films are 60 seconds or less. They were originally gonna be 15 seconds max! That would have changed a lot of things but it’s also an example of using the limitations of the platform as an advantage. I had to construct the strongest film possible within a week and within a 60 second timeframe. I also felt that there was more room to cheat with a smaller picture image. People are only watching it on their phones, and you couldn’t scale up video on Instagram back then. I didn’t need to do massive cleanup work on all this stuff because of that.

I did clean them up afterwards when I decided that maybe I should submit some of these to festivals. I let it be sloppy otherwise.

I went through revisiting a lot of your films. I was kind of going, ‘Wow these are, short! How does a festival deal with this?’

I didn’t realize that the best animation festivals in the world were free to submit to so when I found that out I figured I had nothing to lose. Part of the Area 52 mission was to make a film for what the average cost of the film festival submission fee would be. Around $35 in my estimation. That was essentially my average budget for each of the Area 52 films I made.

But just like you, I kind of figured festivals are not gonna be able to program a 45 second film. It turns out I was wrong, and I’m glad for that.

Do you monetize your work?

Not really. I had distribution initially but the company changed its focus and my films aren’t promoted any longer. But I’ve already resigned to the idea that making money and making films are separate for me. I have no delusions of grandeur as far as that’s concerned. I don’t even have delusions of mediocrity in that way. If it happens, it happens.

I view filmmaking as simply something I like and want to do. I don’t want to ever be beholden to lack of finances. Firstly, you can do experimental films without a lot of money. Indie animation, especially experimental work, doesn’t have to be expensive at all. The way I see it, if I’m going to spend the time that is required to do animation and sacrifice the things that you need to sacrifice in order to make and complete this sort of stuff, then I’m just gonna do it absolutely 100% my own way. Especially being that the industry itself likes to consistently remind us that there is not much room for people like me. I’ve turned that into a source of liberation. We can actually do whatever we want, how we want, if business is removed from the equation.

The industry tells us that if your work cannot be parlayed into merchandising, or if you don’t have a recognizable known actor in your film, or a known musician doing the music, then your chances are slim. There’s no one to distribute these kinds of films to as far as industry is concerned.

The music business is also a shit business but at least the major record labels have smaller, subsidiary labels for distributing to niche markets. Punk rock records generally are sold to that specific audience through a channel meant for them. Same for jazz. Same for electronic music. These are not A-list artists. These are indie artists having records distributed to their audience, therefore their audience wants to come and see them when they travel to their city. There is no equivalent of this for indie animation in the U.S. It’s better internationally but still extremely difficult.

There are no Bad Brains of animation. (referring to John’s Tee Shirt of the 80’s band)

There are though! When I think young, fresh, raw, exciting indie animation I think of artists like Jeron Braxton and Sophie Koko. It’s just there’s no clear distribution outlets for them like an indie music artist in 2024 would have if they are signed to an indie label.

I think you are talking about how there really is a place for the Bad Brains, metaphorically, but it ties back to your feeling about the larger industry in animation.

I think for anyone who doesn’t already know about indie animation to get excited about it, it would have to be marketed to them as a trend. Like, “you’re not gonna be cool unless you engage with indie animation” in some sort of way. Like they did with fidget spinners and Chia pets.

I think that’s the only way that people are gonna be interested in trying it out. But, of course it can’t happen without major studio involvement. We would need their marketing muscle for such an undertaking which means they’d have to be able to parlay some value from already finished indie films with no known actors or dialogue. Not likely.

I mean, some people might say that’s a nihilistic sort of approach. But you’re kind of viewing it as a strength.

It’s abnormal for indie animators to make a feature film because of the time and resources it requires to make one that is worth watching and worth making. So most of us are stuck making shorts and you have to really love making them because that’s the main return on your investment. Otherwise you’re going to feel like it’s a dead end. Pretty sure David OReilly stopped making films and went a different path for this reason.

Right now you’re working on a feature film. You’re stringing together several shorts. You describe your film as sort of an album, which is also interesting.

It’s a feature-length anthology called Films For No One. It’s sort of like an album in the way that an album of music is a group of songs presented together, this is a group of original short films presented together. The idea is that you can watch one long piece with all films strung together somehow. But, you also can watch the shorts individually as self-contained films – similar to “singles” from an album – and not necessarily need to have the context of the entire thing in order for those individual films to make sense or to be enjoyable. You might only watch one film and never see the other films in the group. And that’s okay. I like the a la carte nature of it.

When are you looking to release the film?

Hopefully by the time I’m 50 lol. I’m 46 now. In the next four or five years probably, maybe?

I don’t know. I’m not in a hurry. I’m finding enjoyment in the act of creating and taking my time.

You really make these films just for you, basically?

Basically, but also not. I wouldn’t make films if they were 100% only for me. I would never put myself through the torture of making a film just for myself. Art is meant to be shared.

I don’t want people to get confused by the title Films For No One. I don’t want people to think that I don’t want anybody to see them lol. It’s not that they are only for me, it’s more that I don’t know who they are for. If there truly is no market for these types of films, then who exactly watches them? There is no built-in audience. There also aren’t too many real life examples of successful indie animators making money from their films so that they can make more films. Bill Plympton? Patrick Smith, maybe? Who else? Indie animation doesn’t really have too many filmmakers like Jarmusch and Cassavetes, you know?

Do you do gallery shows?

No, but I totally would. No one’s ever approached me about it. I would go after it but it takes time to submit and present your work well and you need to be focused on only that. I have to stop intermittently to work on commercials or other client work for money. I’d rather spend my other time just making stuff.

I guess the thing with the galleries too is that’s not an easy business either, you know, to even get in with the galleries. There’s certainly another set of weird standards and narrow parameters to contend with and hoops to jump through in the gallery world, just like film.

What do you feel like needs to be covered that you want people to know about?

That you can follow along with the making of Films For No One on Instagram HERE.

Well, I’ve taken up at least an hour of your time. Do you have anything you want to add?

Yes, I would say I’m glad that organizations like ASIFA exist! They are able to facilitate some sort of community for independent filmmakers. I think it’s probably the only institution that I can think of where it actually brings together the Hollywood side of things and the independent side of things—where there’s a common denominator. We’re all filmmakers who love animation. Anywhere else, there’s a big separation between the business side and the independent side.

Even if you go to a festival like Annecy. It’s a beautiful festival but in this respect it’s pretty segregated. They have their market side called MIFA, way over there. And then there’s the independent filmmakers way on the other side of the grounds. There is some overlap of course, and that’s nice to see, but not too much intermingling of the industry side and the underground side in my experience there. So it’s nice to see that there’s a long lasting institution that kind of evens the playing field in some way.

Thanks for having me, ASIFA!